HATTERAS — Core samples from a decades old oil test well near the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse that was abandoned as a dry hole in 1946 will get another look as part of the state’s effort to expand oil and gas exploration, state officials say.

Officials with the N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources said last week that samples from the test well, one of several drilled in a search for oil on the coast from 1920s to the 1950s, show enough of a presence of oil to warrant further investigation.

Supporter Spotlight

Re-evaluating the well near the lighthouse is part of a larger, statewide assessment by DENR of the potential for oil and natural gas exploration after the N.C. General Assembly passed an energy policy bill last year.

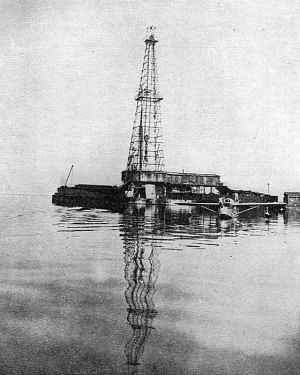

This 1946 photo shows the test well that Standard Oil of New Jersey drilled near the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse. Photo: Bulletin of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists |

Legislators budgeted $550,000 over two years for testing at potential sites throughout much of the state. DENR’s plan centers on expanded testing in Piedmont and mountains counties that have been identified as having the highest potential for the hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, for natural gas.

The assessment plan also included testing in several other areas of the state, from rock fragments in the western mountains to the rift basin in Pasquotank, Camden and Bertie counties in the northeast coastal plain.

Since the bill passed, the prospect of expanding testing for oil and natural gas has drawn opposition, especially in mountain counties where western legislators in both parties have called for a halt to the tests and for DENR to concentrate on areas already identified as having potential.

This year, after first announcing that they would move ahead with the full program of statewide testing once the budget was in place, DENR officials have scaled back the plans, eliminating the tests in the western mountains and the three coastal counties.

Supporter Spotlight

On the coast, the only project still on the list is Hatteras Light Well No. 1 that was drilled seven decades ago. Jamie Kritzer, a DENR spokesman, said driving the project, which is being led by the N.C. Geological Survey, are results from work done over the past two years by researchers with U.S. Geological Survey and Texas A&M University on a similar coastal well drilled in Pamlico Sound in 1947.

“What we found is an indication of the presence of oil in that well,” he said. “Based on that and the technical improvements since 1946, we opted to go ahead and study [the Hatteras] well.”

Kritzer said the department plans to issue a request for proposals this fall after the new state budget is certified. DENR has budgeted $21,000 for the project, with $7,000 coming from the state Geological Survey budget and the rest from federal grants from the U.S. Geological Survey and the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management.

There are no plans for further exploration at the well site itself, Kritzer said. The original core sample will be analyzed using modern techniques to determine if oil or natural gas exists at the well site, he said. The new analysis could also provide clues to what resources might exist offshore.

The examination, which could take up to two years, will become part of a larger assessment for the legislature on the potential hydrocarbons resources statewide, Kritzer explained. He said it will be up to the legislature and other state policy makers to decide how to proceed from there.

One certain use for the information, particularly if it indicates the presence of oil, is in the state’s ongoing effort to encourage offshore exploration.

A 2013 legislative memo outlining the rationale for each of the regional assessments for oil and gas potential said the Hatteras well study “has direct bearing on the potential for offshore hydrocarbon exploration and potential hydrocarbon accumulations in state and federal waters.”

Brief History of a Deep Well

This 1947 photo shows the test well that Standard Oil drilled in Pamlico Sound near Hatteras Island. Photo: Bulletin of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists |

The Standard Oil Company of New Jersey drilled the Hatteras Light Well No. 1 to a depth of roughly 10,000 feet in an attempt to map the petroleum potential of the region. A 1946 photograph shows the well assembly located in the dunes just south of the emblematic lighthouse.

Standard Oil, which used the brand name Esso, in 1973 renamed itself the Exxon Corporation. That company merged with Mobil Oil in 1999 to become the modern ExxonMobil.

The well was much deeper than previous wildcat attempts, cutting through sand, shell gravel, clays, limestone and shale, revealing a rich fossil history that would later be used by researchers of pre-historic coastal flora and fauna.

After the well testing ended, some of the core samples from the Hatteras Light well were shipped to the N.C. Geological Survey in Raleigh for storage. In the January 1950 edition of the Bulletin of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists, Walter Spangler, describes the Hatteras Light Well No. 1 as the “deepest well drilled to date along the Atlantic Coastal Plain from Main to Florida.”

Spangler writes that the well was 1,696 feet southwest of the former location of the lighthouse, which was moved to higher ground in 1999. It was started on Dec. 1, 1945, and abandoned as a dry hole on July 19, 1946. Afterward, samples were distributed to other oil industry and academic researchers.

A year later and using the same equipment, Standard drilled another well in a section of Pamlico Sound described by Spangler as “11 miles south of Wanchese and 3 1/2 miles west-northwest of Pea Island Coast Guard Station.”

The Pamlico project began on Jan. 7, 1947, and was abandoned on March 13, 1947. Drilled to a depth of 6,410 feet, it too was considered a dry hole. After the tests, according to Spangler, “the company abandoned all activity along the Atlantic Coastal Plain.”

Old Data With New Eyes

Ken Taylor, the state geologist, said Standard’s strategy for the two East Coast wells was to “find the biggest pile of sand they could” and drill down into it.

The new search for oil and gas potential is quite a bit different, he said.

Taylor said his goal is to provide the clearest picture of what the samples from the well’s “mud log” indicate.

Ken Taylor |

He said the tests would be similar to those performed at Texas A&M on the Pamlico Sound well samples. Rocks in the samples are dissolved in solvent, the solvent removed, and the material then goes through a battery of tests for composition. Researchers will be looking for presence of oil, methane and other chemicals present when petroleum breaks down.

If those chemicals are found and how deep below the surface should provide another key to understanding the fossil fuel resources offshore, Taylor said, such as how the oil got there and where it might have migrated.

Taylor said he understands that the study could raise concerns given the long running controversy over offshore oil and gas development. But he stressed that as state geologist, he’s charged with accurately detailing the state’s mineral resources.

“What we’re looking for is the presence of oil,” he said, “not whether there’s enough for production, but presence.”

He said the Hatteras well study will provide another important data point in the study of the state’s offshore potential. That, he said, could prevent “bad assumptions” on the part of policy makers. Right now, Taylor said, anyone can put any number they want on the potential of offshore resources.

“We’re trying to develop reliable information,” he said.