The crew fishes for sharks 12 miles offshore off Shackleford Banks in Carteret County as part of the Frank Schwartz’ survey for UNC’s Institute of Marine Sciences in Morehead City. The 42-year-old survey helps assess the health of shark populations. Photo: Tess Malijenovsky |

MOREHEAD CITY – It was rough seas for a day of shark fishing, one that makes waves in your stomach — and not because you’re “sharkin’,” as the captain put it. The bow of the 48-foot research vessel seemed to reach for the sky before dropping nose-first down into a wave. At times it looked like we were going to dive straight into those dark open waters before the next wave lifted the boat again.

That is, at least, for the new kid on the boat. The seasoned crew dressed in green waders and orange gloves stepped steady and deliberately across the stern, which has an opening flush with the ocean, as they hauled and released a trawl net of fish onto the deck, bait for our larger prize. The scent of diesel fuel and fish, the deep drone of the boat engine, not even the cool, salty breeze could take my mind off what prehistoric predator might be lurking down below. What would we catch today?

Supporter Spotlight

“We don’t worry too much about it stormin’,” said Capt. Joe Purifoy.

Purifoy and his crew make the biweekly pilgrimage to the waters off Shackleford Banks in Carteret County to catch sharks for Frank Schwartz, a researcher at the University of North Carolina’s Institute of Marine Sciences in Morehead City. The routine is almost always the same: They trawl for small fish to use as bait and then they reel out about a mile of monofilament fishing line with dangling baited hooks. They fish at two places, a mile-and-a-half and 12 miles offshore.

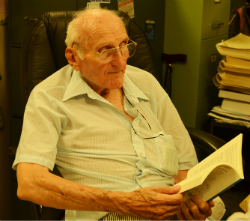

Frank Schwartz leafs through his book Shark, Skates, and Rays of the Carolinas in his office at UNC’s Institute of Marine Sciences. His shark survey is the longest continuous shark dataset in the country. Photo: Tess Malijenovsky |

“I wanted to find out what we have out here,” said Schwartz, who began surveying sharks off the N.C. coast in 1972 and who’s going on his 47th year working at the institute as an ichthyologist, or fish scientist.

Schwartz, 85, has more than 1,300 trips under its belt, making his shark survey the longest continuous dataset in the United States that uses the same gear at the same locations.

Schwartz intercepts sharks on their seasonal migrations. Over the years, then, he’s been able to detect the types of sharks that visit North Carolina’s coast and gauge population trends. Most importantly, the survey provides a historical perspective in assessing the health of shark populations today.

Supporter Spotlight

Schwartz says there are certain species that he isn’t seeing anymore, particularly the large sharks. He thinks the decline is cyclical and isn’t worried that any one species will go extinct. However, other scientists think sharks are indeed in serious trouble; and despite recent studies indicating that some sharks are very slowly beginning to recover, their threat of extinction is still real.

George Burgess is one of those scientists. He directs the shark research program at the Florida Museum of Natural History and is the curator of the International Shark Attack File. “Shark populations have been under stress through a variety of sources, most notably commercial fishing but also in certain areas of the world such as the East Coast of the United States through recreational fishing and of course also as a result of habitat loss and modification,” he said.

The Early Days of Sharkin’

As soon as the bait from the trawl net hit the deck, the students on board swarmed over the pile, piercing the small fish with fat, rusted hooks. Students often come on the shark survey trips to record the measurements, the sex and the species. All captured live sharks will be tagged and returned to sea.

The Cape Lookout Lighthouse was a thimble on the horizon when the men began deploying the fishing line in an assembly fashion. One controlled the spool of line with a wooden stick, one took a seat on the edge of the boat to pass the baited hooks in order while another clipped orange buoys onto the line after every 15 hooks. Then it was a matter of waiting.

According to Schwartz, the decline in the populations of certain shark species off the N.C. coast is a natural fluctuation. “One species goes down, another will come up,” he said.

Frank Schwartz uses a wooden measuring stick to size the 14-foot dusky shark caught on his survey in 1991. Photo courtesy of Frank Schwartz. |

“As I say in the last sentence of my book, they’ve been around for 400 million years and I think they’ll be around for 400 million more years,” Schwartz said.

His book Sharks, Skates, and Rays of the Carolinas, published in 2009, is an illustrated guide that covers the 91 species of sharks, skates and rays found off the Carolinas.

For some of the larger species, however, the decline is undeniable to Schwartz.

“[The dusky] shark, that big one, its population is crashing now. I don’t think they’ll go extinct but it’s crashing,” he said. “Whereas before we could catch in a day 20 to 30 of them, now I haven’t seen one for five years.”

“Silky sharks is another one that’s disappearing on us,” he said. “We’re not seeing them anymore.”

Schwartz recalls the shark fishing clubs in Carteret County in the mid-1980s, a time when as many as nine commercial boats fished for sharks. The flesh could be eaten, the skin used for leather, the liver oil extracted for vitamins or the fins sold in Asia, where shark fin soup is a symbol of wealth and class in China.

“In 1981 we had what was called a shark jubilee here and in Texas. We had hundreds and hundreds of sharks here along the beach feeding, all kinds of sharks,” said Schwartz.

The beaches were closed for three days during that event. In that decade alone, Schwartz surveyed about 3,400 sharks on the research vessel and as many as 14 species a year.

“I could take you out there and in five minutes give you five to 10 tons of dogfish sharks. You could go out there now and you’d be lucky to get six,” Schwartz said.

Who’s Attacking Whom?

“Virtually every species of sharks on the [western] Atlantic have declined with a couple rare exceptions,” said Burgess.

A 2007 statistical analysis of Schwartz’s survey revealed a drastic decline in the number of the larger sharks at the top of the food chain: 87 percent decline for sandbar sharks; 93 percent for blacktips; up to 97 percent for tiger sharks; 98 percent for scalloped hammerheads; and 99 percent or more for bull, dusky and smooth hammerhead sharks. Such number, the analysis noted, “implies their likely functional elimination.”

The scalloped hammerhead became the first shark species protected by the U.S. Endangered Species Act.

A group of shark specialists for the International Union for Conservation of Nature, the world’s most comprehensive inventory of global conservation statuses, recently found that a quarter of sharks, rays and other cartilaginous fish are threatened with extinction. The group is at a “substantially higher risk than most other groups of animals” and has the “lowest percentage of species considered safe,” about 23 percent are classified as “Least Concern.”

This artistic rendition of the “Jaws” movie poster depicts how the tables have turned. The decline in sharks is largely due to overfishing, bycatch, habitat loss and their biology. Image: Jelsin Alvaro |

In an article released this year by the group, a co-chair for the shark specialist group, Nick Dulvy, said, “Our analysis shows that sharks and their relatives are facing an alarmingly elevated risk of extinction. In greatest peril are the largest species of rays and sharks, especially those living in shallow water that is accessible to fisheries.”

Part of the reason sharks have been hit so hard is because their biology is working against them.

“The problems that sharks and rays have is that once they get down they stay down for decades rather than years whereas most bony fishes under proper management can recover in five to 10 years at most,” said Burgess.

Sharks reach sexual maturity late, and many can be pregnant for 12 to 24 months. Those with longer pregnancies reproduce once every two to three years and females have few pups at a time.

Sharks will live for a long time, most species for 10 to 30 years and some even longer. Great whites can live as long as 70 years or more. Schwartz said he is still catching sharks with tags from 1972: “2011 was the last one,” he noted.

Being the best hunters in the ocean can have a downside. “They’re actually pretty easy to catch because they’re so damn efficient at finding bait and will take a hook so readily,” said Burgess.

Gill nets are also extremely effective at killing sharks as well as other marine life, he said.

“Certain species are found dead on lines anywhere from 80 to 100 percent of the time,” said Burgess. “That’s the other part of the story — not all sharks are created equal in that respect.”

Compared to those that come up on a line very much alive, like the nurse shark, the species that are more prone to dying during capture are the ones that tend to have a much slower recovery rate, like hammerheads. As an example, dusky sharks, which used to be quite common on the N.C. coast in the early 1970s, is a large coastal shark with a three-year reproductive cycle that is probably down to 10 or 20 percent of its original biomass, said Burgess.

Sharks Help Balance Our Oceans

When it started raining, we were 12 miles offshore and nearly finished reeling in the second line. Hook after hook came up to the boat empty. After a half day at sea, only three sharks less than three-feet-long were caught: two Atlantic sharpnose sharks and a small blacktip. The sharpnose, which has white spots and averages about three feet, is one of the most common sharks off the N.C. coast in the summertime and their pups are often caught off the piers. It can recover two to three times faster than its kin because it reproduces every year.

“They’re doing just fine,” said Burgess.

Charles “Pete” Peterson, another researcher at the UNC institute who co-authored the analysis of Schwartz’ survey data, suspects there is another reason that factors in. The only natural enemy of small sharks and rays are the sharks more than six-feet-long, the apex predators. He and other researchers have found that the decline in these larger sharks coincides with an increase in rays and smaller sharks and also a cascading effect down the food chain.

“Sharks, as we discovered in our work, play a very important role in the balance of nature in the context of their role as apex predators,” Peterson said.

The Road to Recovery

The Atlantic sharpnose isn’t the only species on the rebound. “Frankly, virtually every shark out there is having some sort of recovery,” Burgess said.

In part, he said, that’s because of different management strategies. For example, closures prohibit fishing in an area during a certain time of the year when a particular species, like the dusky, is likely passing through on its migration.

Students work quickly taking measurements of the sharks so they can return them to the ocean as quickly as possible. Photo: Tess Malijenovsky |

Or, the rise of great white sharks on the East Coast is because it’s listed as a “prohibited” species to catch by the National Marine Fisheries Service and also because the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972 protects the sharks’ favorite foods – seals and sea lions.

Shark sittings are becoming less rare thanks to more people in the water with cameras on their cell phones and a means to instantaneously share a shark siting with the world on social media. However, contrary to dozens of media headlines, that doesn’t mean that there’s been an “explosion” or “surge” in the populations of great white sharks, Burgess said.

“The most difficult thing, I think, is getting people to realize that recovery is such a prolonged process,” he said. “What we’re seeing perhaps is a slight increase in sharks.”

Another thing we’re seeing is that the public opinion about sharks is shifting.

“After the 1975 release of the movie “Jaws,” the general public felt that ‘the only good shark was a dead shark,’ however in the 30 years that have followed, this mentality has changed,” said Neil Hammerschlag, co-author of a study on the economic value of shark ecotourism and the importance of including conservation efforts in long-term management plans. “A growing number of people are turning their fear into fascination and want to continue to see sharks in the wild.”

According to the study, a single reef shark could be valued at $73 a day alive or more than $200,000 over a conservative 15-year life cycle. That beats the one-time value of a pair of fins for shark fin soup, which can range from $50 to $1,000 a bowl.

“[Sharks] are part of the wondrous biodiversity of life on the planet,” said Peterson. “By persisting and exceeding they provide wonder to us all. Sharks are a fascination for people that exceeds most other groups of organism, so absent the sharks from nature we’ll lose all that particular form of enjoyment that we get from the diversity of sharks and the stories associated with them.”

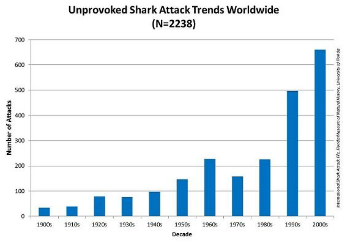

| Are Shark Attacks Increasing off the N.C. Coast?By Tess Malijenovsky There will likely be more shark attacks per year in the future here along the N.C. coast. Though, experts say, an individual’s chance of being bitten will decrease. Over the last 20 years, there’s been an upward trend in the number of shark attacks, says George Burgess, the curator of the International Shark Attack File, and he suspects there will be more “incidences” this decade than the last.

People aren’t the only ones braving the water later into the winter season or further up the coast. As ocean temperatures continue to rise, many species are expanding their distributional range. “With the increase in water temperatures, one will expect there to be increases in the number of sharks along the East Coast of the United States, including North Carolina,” says Burgess. “You’re going to have more sharks in more areas encountering humans,” he says. “As a result the answer is, of course, there will be more of these incidences because a) you’re going to have a lot more people in the water and b) you’re going to have more sharks in areas where they were not normally found. We’ve already seen that in certain areas.” Burgess references a series of great white shark attacks near Russia in the northwest Pacific, where neither great whites nor people used to swim because it was too cold. Don’t freak out yet. Burgess says, “Our chances of being bit as individuals actually decreases each year because of the sheer volume of people in the water. “Despite the fact that there’s less sharks in the water, we still continue to get an increase in the number of attacks, and that’s simply because we’re putting so many people in the water,” Burgess said. 12 tips to reduce the risk of a shark encounter:Tip compiled by the International Shark Attack File

|