Water TipsHealth experts recommend a few things for those who frequent the waters, especially during periods of heavy rain, even in freshwater:

Tips for algae include: Supporter Spotlight

|

MOREHEAD CITY — A Jacksonville mom this month went on her Facebook page after nearly two weeks of rain to ask if it would be safe to take her kids to the coastal waters of Carteret or Onslow counties.

Some respondents’ posts said “yes,” some said “no” and some just conceded they didn’t know. The mother ended up taking her kids to a water park “just to be on the safe side.”

That same week, April Clark, owner of Second Wind Ecotours & Yoga of Swansboro, was taking some customers on a kayak trip to Jones Island in the mouth of White Oak River when one of the kayakers saw a reddish coloration in the water and wondered aloud if it was safe. There had, in the wake of the drenching rains, been reports of algae blooms to the south, and the state had placed advisory signs at various locations, essentially warning folks to brave the bacteria-laden waters at their own risk.

Other customers, Clark said, had been hesitant to take to the water at all, given that the state had posted those advisories against swimming at numerous sound and ocean beach access spots along the coast from Dare County south to New Hanover County.

Other customers, Clark said, had been hesitant to take to the water at all, given that the state had posted those advisories against swimming at numerous sound and ocean beach access spots along the coast from Dare County south to New Hanover County.

“It was very worrisome,” said Clark, who is a member of the boards of directors of the statewide N.C. Coastal Federation and the White Oak-New River Alliance, two organizations that have long been in the forefront of the fight for water quality in the central coastal area.

Supporter Spotlight

“It cost me some business, and if we don’t do something, it’s going to cost me and many others a whole lot more. Good water quality is what we all count on for our livelihoods and for our recreation.”

What concerned Clark most was not that the heavy rainfall forced the state to put up signs – it’s not all that unusual – but that the signs might point to even more serious problems on the horizon.

“You don’t see it so much if you’re in a (power) boat, but when you’re in a kayak, you can really see the sludge on the bottoms of our river (White Oak) and the creeks,” she said. “Then the state gets these high bacteria counts after rain and puts up the signs, and you wonder if this is something that’s going to happen more often, if it’s something we’re just going to get used to seeing.”

The N.C. Recreational Water Quality Program, which put up those signs, operates as part of the Shellfish Sanitation Section of the state Division of Marine Fisheries, headquartered in Morehead City. It’s the same agency that opens and closes shellfish harvesting waters to ensure the safety of the oysters and clams sold to consumers.

According to J.D. Potts, who heads the recreational waters program, the 27 advisories since June along the N.C. coast has been the worst spell, absent a hurricane, in quite some time, truly more akin to the contamination and necessary precautionary measures taken after hurricanes that affect the whole length of the state’s coast. While unusual, however, it’s not unique.

“It reminds me of one we had in September 2010, when we had 12 to 15 inches of rain in a relatively short time,” Potts said. “There was also a time in 2000, I think, when we had 10 or so inches of rain in July and 10 or so more in August.

The program tests 240 swimming sites, most of them on a weekly basis during the swimming season, which runs from April through October. Testing is done less often at other times of the year. Water quality sampling results for all locations are posted on the program’s website, along with an archive of past swimming advisories.

The agency, according to Potts, tests for enterococcus bacteria, which are found in the intestines of humans and other warm-blooded animals and are an indicator of human waste. While it will not cause illness itself, its presence is correlated with that of organisms that can cause illness. If bacteria levels exceed the state and federal standards, Potts said, the staff sends out a press release to inform the public and an advisory sign is posted at the swimming site.

Those signs blossomed like mushrooms in yards after the recent bout of rain.

“This time we had 10 to 15 inches, in some places five inches in one day. There was so much in Onslow and Carteret that we decided to do that precautionary advisory,” Potts explained. “It generated a lot of publicity and people were talking about it a lot.”

The chatter is certainly understandable. “Waters impacted by these storms can contain elevated levels of bacteria that can make people sick,” Potts noted in a press release. “Floodwaters and stormwater runoff can contain pollutants such as waste from septic systems, sewer line breaks, wildlife, petroleum products and other chemicals. People should avoid swimming near stormwater outfalls and inlets as these areas tend to have concentrated amounts of pollutants.”

Potts noted that because the waters affected were widespread, advisory signs might not be posted in all swimming areas, but the public should avoid swimming in sound-side waters until testing indicates that water quality meets Environmental Protection Agency’s standards. Test results of samples taken from ocean waters have not indicated widespread problems; however, the public should avoid swimming in areas where floodwaters are being pumped into the ocean surf, Potts added.

The source is mostly from stormwater runoff, not from industrial or sewage discharges. Rain washes over impervious areas like streets, roofs and parking lots, picking up bacteria from wildlife before draining into water bodies. There are other areas where direct discharges are a problem.

April Clark |

Frank Rush |

He emphasized that the state does not, as some mistakenly believe, “ban” swimming at sites were either permanent or temporary signs are posted.

“What we do is give people the information they need to make an informed decision,” he said. “But it is up to the individual.”

Neither the state, county nor any municipality actively enforces swimming advisories. That, Potts said, can be done only by a county or state health director; and to Potts’ knowledge, it’s never happened. He’s fully aware that “some people heed the advisories, some don’t,” and some seem to pick a middle route, maybe wading instead of swimming and going under the water.

The system seems to work – there are few health problems reported – but it also can be a bit confusing and causes some consternation for not just business owners and families but also for local government officials in towns where folks depend on clean water for their livelihoods.

Emerald Isle Town Manager Frank Rush, for example, said beach-goers often don’t fully understand that the advisory signs are very site-specific. Although the signs clearly state that the warning only applies for 200 feet in either direction, many still don’t realize that the danger, if there is any, is supposed to be confined to that area.

“We do get a lot of questions about it and so do our lifeguards in the areas where we have them,” Rush said. “If I’m asked, I’ll usually say that the sign is an ‘advisory,’ that in the end it’s a personal decision, a choice between the risk of exposure and the benefit of enjoying the water.”

At the same time, Rush said, he and others who are questioned by beach-goers most of the time tell people that it generally makes sense to heed the advisory and just move 200 feet in either direction from the sign.

“It’s really not that big an inconvenience to do that,” he said. “We certainly don’t want anyone to get sick, so you don’t want to tell people just to ignore the advisories.”

Still, Rush said, “I wish we could all get together and somehow figure out a way to better convey to people that the advisories are for small areas, and that for most people, the risk level is really pretty low and that even during these things, almost all of our waters are pretty pristine. We’re very fortunate.”

Potts agreed and stressed that North Carolina in general has very clean coastal waters, especially in comparison to many other, more urbanized, resort areas. In fact, the National Resources Defense Council placed North Carolina fifth of the 30 coastal states in its 2014 ranking of clean and healthy beaches.

“Even with all the rain we just had, almost all of our beaches tested fine, especially on the ocean side,” he said. “But there’s no question it all got a lot of publicity.”

Clark, the kayak and yoga business owner and environmental activist who lives and works in Swansboro, said it’s true the publicity is a problem for businesses. Customers, she added, are attuned to stories from elsewhere too, such as news accounts of the sometimes deadly vibrio vulnificus bacteria in Florida and Washington D.C. and recent reports of potentially toxic algae in North Carolina waters.

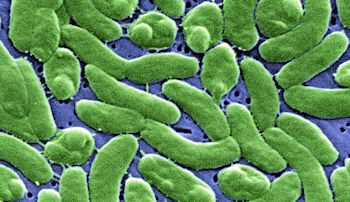

Steve Murphey, environmental program supervisor within the shellfish sanitation section, said it’s true that vibrio vulnificus is present in some North Carolina waters and that it thrives when the waters are warm.

However, he said the bacteria are most often found in the more brackish waters, upstream from the coast in rivers and creeks, and are less prevalent in the higher-salinity ocean and the sounds.

In addition, Murphey said vibrio vulnificus is most problematic for people with impaired immune systems – those who suffer from cancer, diabetes or cirrhosis of the liver, for example – or who have open wounds.

There has been at least one death from vibrio in the region in recent years; a Fairmont man fishing in Little River at the North Carolina-South Carolina border died after he cut his leg and contracted the bacteria when he washed the cut with water from the river. And Murphey said vibrio vulnificus is often found in shellfish from the state’s waters, but generally poses no threat unless people with compromised immune systems eat raw shellfish. There are no documented cases of vibrio deaths from North Carolina shellfish, he said, although one North Carolina man did die from eating vibrio-contaminated shellfish from another state.

The bottom line on vibrio vulnificus, Murphey said, is that, “We know we have the bacteria and people should always take the necessary precautions.”

The bacteria vibrio vulnificus as seen through a microscope at 13,000-times their actual size. Photo: Centers for Disease Control |

State officials detected algal blooms near ocean piers at Topsail Island, but they moved offshore.

While it’s safe to boat or fish in the affected areas, health officials routinely encourage the public to avoid contact with large accumulations of the algae and to take precautions to prevent children and pets from swimming or ingesting water in an algal bloom.

Algae, generally speaking, are a good food source for many aquatic organisms. But big blooms pose problems and serve, experts say, as a kind of canary in the coal mine, a signal that something is wrong.

When hot temperatures and calm winds combine with waters rich in nutrients, such as nitrogen from stormwater that has washed off fertilized farm fields, nutrient-rich waters, large algal blooms may form that can produce toxins that pose a human health hazard. And when the algae decompose, the process robs the water of oxygen and leads to fish kills.

None of this, Clark said, paints a pretty picture for the future of water-dependent businesses along the North Carolina coast. People need to embrace the steps necessary to safeguard and improve overall water quality, she said. Developers need to implement buffer zones and other storm water management practices, and homeowners and business owners need to retrofit solutions to prevent runoff, if possible, Clark said..

“It’s all about awareness and education,” which is what environmental groups like the federation and WONRA are all about, Clark said. “If we don’t do something, it will affect tourism. A sick river indicates a sick community. We all need to take whatever small steps we’re able to take, but a lot of people don’t even know there’s a problem and don’t know what solutions are available.

“All of this is a wake-up call for us,” she continued. “We (at Second Wind) try to do our part. When we do our paddles, we pick up trash. We want people to notice, because if you notice, then you’ll want to do something.”