Ernie Foster runs the Albatross Fleet on Hatteras Island and serves on the N.C. Coastal Federation’s Board of Directors. Photo: The Albatross Fleet |

HATTERAS — If anything illustrates Ernie Foster’s fishing heritage on Hatteras Island, it’s the Albatross Fleet’s net house, a weathered wooden building near the Foster family home and graveyard.

“Everyone who fishes – you need somewhere to store your nets,” Foster said, opening the door to a room filled with shelves of vast cotton and nylon nets. In racks on the ceiling and walls there were dozens – maybe hundreds – of fishing rods and reels going back to the 1930s, when his father Ernal Foster launched the Outer Banks’ first charter fishing operation.

Supporter Spotlight

“This was hand-tied by my grandmother,” Foster said, picking up a piece of the white cotton net, appearing as intact as if it were tied yesterday.

On another shelf, Foster managed to find the net gauge that his grandmother used to size the 2½-inch mesh. The gauge was essentially a wood block that the netting was wrapped around and knotted. He said he hopes that a use can be found someday for all the nets and retired fishing rods.

“I keep saying, ‘Well, I’ll use the guides,” Foster said about the old wooden rods. “I hate to throw something away that possibly has a need.”

Preservation and heritage have long been important to Foster. Both will suffer, he knows, without a clean environment. As a member of the N.C. Coastal Federation’s Board of Directors, Foster, 69, serves as representative of the coastal heritage of Outer Banks watermen. He also has become a spokesman for a community that interacts with the coastal environment each and every day all year round.

Even among those who are outspoken critics of conservation groups they blame for onerous regulations, Foster said, the federation’s non-confrontational approach to issues has helped it be effective on the Outer Banks and with members of the fishing community.

Supporter Spotlight

“I think my favorite evaluation is, ‘They’re not that bad for an environmental group’,” Foster said. “That is high praise. There is a high level of respect.”

Foster already has the historic standing to give him credibility in his tight-knit community. His father was the entrepreneur who cleverly launched the now-huge charter fishing industry on Hatteras Island in 1937. Foster has become a go-to person for comments on the island’s heritage and recreational and commercial fishing issues.

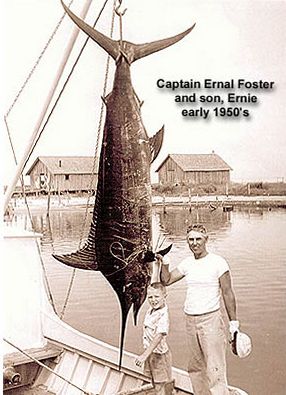

Ernie Foster pictured with his father, Ernal. His father launched the first charter fishing operation on the Outer Banks. Photo: N.C. Watermen United |

With his dry sense of humor and deep knowledge of the island and its issues, the loquacious and opinionated Foster has become a media magnet, interviewed for television news, quoted in newspaper articles, appearing in documentaries and featured in magazines. Unfailingly, he defends the island’s fishing heritage and rails against anything that he believes threatens the island’s environment, traditions or livelihoods.

He has little patience with critics who judge Hatteras folks as fools to live on the little island where their ancestors are buried in their backyards and tropical storms present annual dangers.

Hatteras has a long history of coping with storms, he said, but villagers are not silly enough to live in huge oceanfront mansions. “One pine tree in a suburban neighborhood causes a lot more damage than seven shingles blowing off my roof,” Foster said. “That’s pretty much what I see, in large measure.”

When he was student at N.C. State University, Foster said that ecology was a new word. The concept, however, was familiar to him; that’s the way his father raised him.

“He would never throw anything away,” Foster said. “He did not believe in wasting anything. He would not cut a tree that didn’t need to be cut.”

His father also taught Foster to only catch the fish you needed. “He did not believe in killing for the sake of killing.”

In 1958, his uncle Bill Foster released the first billfish ever released off the coast, leading to the practice of catch-and-release sports fishing.

“There was always the belief that you didn’t take more than you needed,” Foster said. “We would ask the customers, even before there was a limit, ‘How many do you want?’”

The point was drilled: you don’t plunder the ocean for your own gain; you respect the tenuous balance of nature. “It just made sense – it was pragmatic,” Foster said. “As long as there were fish there, you could go back and catch a few.”

After graduating, Foster taught high school physical sciences and biology in Raleigh and Manteo and later was a guidance counselor. He retired in the 1990s and moved back to Hatteras with his wife, Lynne, to take over the operation of the Albatross Fleet, the three wooden boats his father built between 1937 and 1953.

Peggy Birkemeier, who just started her second term on the federation’s board, remembers Foster as a counselor in the 1980s at Manteo High School, when she was a young mother involved in the PTA. Until she joined the board, she said she did not realize the depth of Foster’s history.

“Ernie brings such a heritage to the board that is critical to the work we do to preserve the coast,” she said. “I think that’s important for the Coastal Federation, to hear that story.”

He also has strong connections to the commercial and charter fishing interests. “Nobody else but Ernie can say, ‘Well, when my granddaddy did this …’” Birkemeier said. “It’s a very unique perspective that very few people can say they have.”

Newspaper clippings and photographs adorn the wall of the Albatross Fleet’s office on the dock. Some of the photos were taken by Aycock Brown, the legendary Outer Banks tourism promoter. The wall shows just how special Foster’s relationship is to the coast. There’s 6-year-old Foster standing next to a record-breaking blue marlin that electrified the sport fishing world. There is him at 13, steering the Albatross with his left foot while casually looking out the window.

“That was easy to do,” Foster said.

Albatross III, one of the three boats that Ernie Foster’s father built between 1937 and 1953. Photo: The Albatross Fleet |

Foster has seen significant change on the Outer Banks, and he is the first to acknowledge that there is plenty good about the improvement in the economy, education and amenities like nice stores and better access to health care. He is also quick to condemn haphazard development, careless stewardship of the environment and blind allegiance to ideology rather than reality.

Fishermen know that sea-level rise and climate change are real, Foster said. And most acknowledge it’s human-caused, and the effects are being seen all along the coast. But still, some refuse to remove their blinders.

“I deal with people all the time,” Foster said. “The knee-jerk reaction of some of the over-the-top fanatics is terrible.”

The biggest challenge for the coast in the coming years, Foster said, will be maintaining water quality. Since all water eventually flows to the coast, water quality here could be directly affected by activities in the Piedmont, the Triangle and the Triad.

“Fracking scares me to death,” he said.

What Foster appreciates about the federation, he said, is the measured approach executive director and founder Todd Miller takes as a coastal watchdog.

“Todd’s ability to do that is special. He looks long-term. He looks at the big picture. He doesn’t let rabid idealism get in the way of the bigger picture.”

The thing about environmentalism that doesn’t work, Foster said, is making policy that has no grounding in what the people who live in that environment see. For instance, fishermen go past a spoil island every day, and it is brimming with black skimmers. Despite that, access to the nearby beach in Cape Hatteras National Seashore is restricted to protect a few skimmers, as if their populations are critically threatened.

“All the fishermen, every one of them, are seeing that and it makes people doubt you,” he said. “When they know you lie about something, why should they believe you about other things?

“And the Coastal Federation doesn’t do that. They try to be as fair and honest and as transparent as they can be,” said Foster.