Staff of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration conduct research in a marsh near their lab on Pivers Island. Photo: Patricia Tester |

Last of two parts

BEAUFORT – The NOAA Lab on Pivers Island near Beaufort attracted the best fisheries scientists in the world, but it was even a destination for locals, for a time.

Supporter Spotlight

“During the 1940s and early 1950s,” according to a history of the lab by Charles Manooch, a retired lab scientist, “the beach and the immaculately kept, park-like grounds at the laboratory were a source of pride for county residents and an attraction to tourists. Families would often spend weekend days and holidays, spreading picnic lunches on the mowed lawn beneath the large live oak and cedar trees and viewing the museum, aquarium and fish collection at the laboratory.

“Children would play games on the lawns and swim in the protected waters of the small sandy beach. During the summer months, when visitors were numerous, some live animals generally were exhibited also.”

But the biggest period of growth at the lab didn’t start until after World War II, as the nation re-found its peacetime footings and the miraculous burgeoning of the American middle class took off. Construction of a new lab began in 1954 and was completed the following year, Manooch noted in his history. A 12-office wing was added in 1957 and a two-story radiobiological laboratory wing in 1964, three years after a new residence for the laboratory director was built.

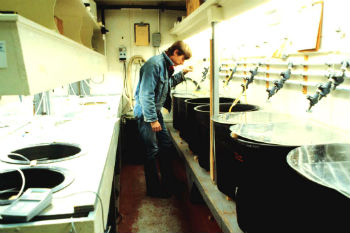

John Burke in the rearing facility, where fish larvae are cultured under controlled conditions for investigations of important aspects of physiology and ecology. Photo: “A History of the Federal Biological Laboratory at Beaufort, North Carolina 1899-1999” by Douglas Wolfe |

Other new construction included shop and service buildings, a physiology laboratory, a computer center and a high-level radiation building. A new two-lane concrete bridge to the island, badly needed for years, was completed in October 1968, and major repairs were made in the last five years.

During the 1950s and 1960s, the laboratory maintained its international prominence in fisheries, ecological and physiological research. Major emphasis during this time was placed on life histories, dynamics and man’s influence on American shad, striped bass, Atlantic menhaden and blue crab. In an era when countries were still testing nuclear weapons by detonating them in the air, lab scientists were also looking for the resulting radioactive isotopes in marine life. Menhaden was also a major focus, as nearby Beaufort Fisheries was one of the nation’s biggest players in the harvest of the fish.

Supporter Spotlight

Gene Huntsman, who lives near Havelock, arrived at the lab in 1967. Science was booming, thanks in part to the emphasis the government had placed on it after President John F. Kennedy launched the country toward the moon in the wake of the Soviet Union’s Sputnik satellite in 1957. Although marine science wasn’t a “new frontier,” there was a lot going on.

“It was an exciting place to be,” Huntsman recalled of his first decade or so on Pivers Island. “The lab was thriving. There were two or three people in every office; we were really falling all over each other. There were a lot of ideas, a lot of opportunities.”

The menhaden program – the lab studied the tiny but highly valuable oil-laden fish closely and worked with a growing industry that satisfied demand for fish oil and fish meal – was hopping, as were early efforts to learn about the reef fish, such as snapper and grouper, which were increasingly being targeted by the fast-growing recreational fishing industry.

Theodore Rice was legendary both for his intellect and for his ability to occasionally drive his colleagues crazy. Photo:”History of the Federal Fisheries Laboratory at Beaufort, North Carolina” by Charles S. Manooch III and Ann B. Manooch |

“There were a lot of brilliant people,” said Huntsman, including those working in the cutting edge radionuclides program.

One of those was Theodore Rice, who became lab director in 1970 and held the post until 1985, when Ford “Bud” Cross took the reins.

Rice, who died in 2011 at age 92 in Morehead City, was legendary, both for his intellect and for his ability to occasionally drive his colleagues crazy.

“He was a Harvard Ph.D., and there’s no doubt he was brilliant,” Huntsman said. “But he was somewhat insecure, and that made him hard to get along with sometimes, because he’d do crazy things. He’d drive us up the wall at times. But eventually he mellowed. And he was a leader.”

There was tremendous interaction in the Carteret County marine science community, said Doug Wolfe, a former scientist at the lab who wrote a book to commemorate its 100th anniversary, and Rice was much of the reason for it. In fact, he said, Rice was in part responsible for N.C. State University establishing its presence, culminating with its Center for Marine and Science Technology, or CMAST.

“He approached N.C. State back in the 1960s and said Duke and UNC were already here, and State should be, too,” Wolfe said.

N.C. State started sending grad students to work and learn in the Beaufort lab, and over the years, before CMAST, adjunct professors from the university taught in the NOAA lab.

As for the UNC connection, Robert Coker was an employee and scientist at the Beaufort lab as early as 1902 and was later assistant commissioner for scientific inquiry for NOAA in Washington. He returned to UNC as a professor in 1923, and eventually founded and was the first director of the UNC’s Institute of Marine Sciences in Morehead City. A building bears his name.

“There are a tremendous number of connections between the early history of the lab and what came later in the area,” Wolfe said. Folks who worked there later were well aware of that, and of the lab’s reputation for excellent science, he said.

“I loved my time at the Beaufort lab,” said Wolfe. “In fact, it wasn’t long after I left – even though it was a promotion – that I wished I had stayed. We kept our place here, and as soon as I retired, we came back.”

Huntsman agreed.

“What I remember most is that people were very dedicated, but everyone liked to have fun. And we were a big part of the community,” he said. “I mean, the community was so small. There were probably only 30,000 people in the county, and only about 5,000 in Beaufort. Everyone knew each other. I think most people liked us but they didn’t necessarily understand us. One fellow… told me that one of the locals put it this way about us: ‘Those people are nice, but their morals aren’t what they should be.’”

John Costlow, who directed the Duke lab and was mayor of Beaufort, was an oversized but loved personality. Photo: Duke University |

It was a colorful place, Pivers Island, in part because of the NOAA lab, but also because of the presence of the growing Duke University Marine Lab, which occupied land sold to the Durham school by the federal government. Duke was home to a growing cadre of fine and renowned scientists, but it also had students, who lived there in dorms and did what college students do.

The late John Costlow, a fine scientist who became mayor of Beaufort and helped usher its reinvigoration through waterfront revitalization and an active and now famous historical association, directed the Duke lab. He was an oversized but loved personality, at times almost Shakespearean, and while the Duke and NOAA scientists collaborated professionally, there was a lot of social interaction, too. It was a humming, vibrant place.

As the 1980s proceeded, some things changed. For example, the federal government’s role in fisheries became more than just research; it got into management. Declining fish stocks put pressure on managers, and managers turned to NOAA for research and statistics that led to rules and regulations.

Some of the local commercial watermen began to think less kindly of the “pinfish doctors” on Pivers Island. Although Huntsman remembers most of the commercial captains as appreciative of the science and the researchers’ dedication to understanding the fish, rules were not popular.

One particularly tough issue arose when the accidental catch of juvenile fish by shrimp trawlers, called by-catch, began to be seen as detrimental to fish stocks. Eventually, North Carolina began requiring trawlers to be use devices to reduce the by-catch. Turtles also became a big issue; trawlers caught them, and most species were listed as either threatened or endangered under the federal Endangered Species List.

The state began requiring fishermen to install devices in their nets to allow turtles to escape. The shrimpers didn’t like them. And NOAA, through its National Marine Fisheries Service, came to be seen, at times, as a villain, responsible for the data behind rules that closed some waters at times and protected turtles from shrimp and flounder trawlers. Those issues are still controversial, but Cross, who was also on the state Marine Fisheries Commission, said he rarely thought that fishermen held him and his scientists responsible.

He also remembers big controversies over mechanical clam harvesting. It was not pleasant, he said, to be in a room when 300 clammers were vociferously clamoring for waters to be opened while others claimed the dredges and boat props were damaging the bottom. NOAA got in the middle of that a bit, before the state finally went with a rotation system that seems to have eased feelings.

A pound net fisherman passes a captured loggerhead sea turtle to laboratory staff for tagging studies. Photo source: “A History of the Federal Biological Laboratory at Beaufort, North Carolina 1899-1999” by Douglas Wolfe |

The lab also was a focus of the entire coast when single-celled dinoflagellate algae, a red tide, hit the Carteret County area in late October 1987. The toxic tide shut down shellfishing waters for months, and much of the research and monitoring took place on Pivers Island.

That work was headed by Pat Tester, who came to Beaufort as an Oregon State University graduate student in 1976, married a local man and ended up working for NOAA as a scientist for 33 years.

Cross said that because of the widely known work of Tester and others, American Indians in the state of Washington eventually asked the lab for help developing a new type of test they needed for their shellfish harvests. The lab successfully integrated molecular work with the normal testing system and were able to solve the problem. Tester is now one of the best known of the lab’s many stellar scientists.

Huntsman and Cross both said that even during the years when fishermen were most angry with federal fisheries managers, most people in Beaufort, even commercial fishermen, generally treated the staff cordially. “I think they valued the fact that we were interested in the (health of) the fish,” Cross said.

He also noted that the fishermen much appreciated the lab’s crucial work to map sea grass beds, which need to be protected because they are important habitat to many marine species.

But the toughest years came later, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Huntsman and Cross said, when tight federal budgets led to staff cuts and even rumors that the lab would be shuttered.

For a time, Huntsman said, “it was like a tomb” and morale was low. But many of those on the staff had been through similar times and thought the bleak period would pass, and it did. The lab thrived again.

Part of the reason the lab survived, Cross said, was strong support from U.S. Congressman Walter B. Jones, a Farmville Democrat who headed the House Merchant Marine and Fisheries Committee. Jones has died, but his son, Walter B. Jones, a Republican, represents the district in the U.S. House of Representatives and is also viewed as a strong supporter of the lab.

In fact, partly because of past budget “scares,” but mostly because of strong local support and backing from politicians like Jones and U.S. Sen. Kay Hagan, a Democrat, neither Cross nor Huntsman thinks the lab’s doors are likely to close.

President Obama recommended in his 2015 budget proposal that was released in March that the lab be closed as a cost-saving measure. A NOAA spokeswoman said at the time that the “aging facility” needed $55 million in work, “exceeding agency budget resources now and for the foreseeable future.” The infrastructure improvements needed, according to NOAA, would be an added expense on top of the $1.6 million the lab needs each year. “The president’s FY2015 budget request addresses this challenge by proposing closure of the lab,” the spokeswoman said.

But the proposal requires congressional approval, and Jones has been working to stop that from happening. Hagan has also said she’d fight the closure to protect jobs and research that helps preserve coastal marine life.

Pat Tester is one of the lab’s best known scientists. She headed the research on toxic red tide. Photo: Patricia Tester |

It should be noted that Congress rarely passes budgets proposed by presidents. The “PresBud,” as it’s called on Capitol Hill, is really just a president’s suggestions for funding priorities and levels. House and Senate budget committees can use it as a framework when fashioning their budgets, but Congress can totally ignore a president’s wishes when passing a federal budget. In fact, the last two Obama budget proposals that came for a vote in the House or Senate were roundly defeated.

Still, Cross said, it’s the first time closure has been “officially” proposed, and there are employees at the lab who have not been through anything like this.

“It’s a little scary,” he said. “And although we don’t really think it’s going to happen, it could. There certainly aren’t any guarantees.”

If the worst did happen, Huntsman said, it would be tragic because the lab still plays vital roles in fisheries science and is staffed by scientists dedicated to “the pursuit of excellence.” The facility, he said, remains a jewel, surpassed by few facilities in the system, and does crucial work involving a number of important federal laws, including the Endangered Species Act, the Sustainable Fisheries Act, the Coral Reef Conservation Act and the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

Cross agreed.

“There would be a significant impact on fisheries research, and not just because of the people here,” he said. “It’s also a unique location. Losing it just doesn’t make sense.”

Wolfe said it’s hard to accept that a lab as often recognized with NOAA awards could be considered for closure, and noted that many top and well-known scientists work there and do important work.

James Morris, for example, is one of the experts on lionfish, an exotic species that has made international news after making its way to North Carolina, the rest of the South Atlantic and the Caribbean, and becoming an unwanted but hard-to-stop permanent guest.

William Sunda received the rare honor of being elected as a fellow by the American Association for the Advancement of Science in November 2011. His expertise is trace metal biogeochemistry in the ocean and has worked to help understand the impact of phytoplankton on world climate.

The bottom line, Wolfe said, is that the closure of the lab would be a serious blow to marine science in a region that is crucial in many ways.