First of two parts

BOLIVIA — You can hear the country in his voice. His slow and deliberate southern drawl suggests an upbringing on a tobacco farm, a childhood in a country church and a crossroad’s hamlet.

Supporter Spotlight

Sitting behind a large office desk, however, wearing a dress shirt with a pen in his pocket and an oversized Carolina-blue gem on his class ring, Steve Stone’s suggests otherwise. This farmer boy now helps run one of the fastest-growing counties in the country.

Stone first became the deputy county manager at the beginning of the new millennium when Brunswick County was the 14th-fastest growing county in the nation. He took what was considered an unusual step at the time by partnering with an environmental group to promote a more natural way to control stormwater, called low-impact development, or LID, and restore the county’s water quality.

Supporter Spotlight

|

LID was all pretty new back then. But what made the move particularly unorthodox was the group Stone chose to align with. County commissioners considered the N.C. Coastal Federation to be their opposition.

“I’ll be honest,” Stone said, “at least some of the elected officials in Brunswick County and some development interests really felt that the Coastal Federation was sort of the county’s enemy, that the Coastal Federation was opposed to development.”

The quickly urbanizing population of Brunswick County was fueling the need for a centralized sewer system. The federation was opposed to the idea because, without proper controls, the resulting high-density development would increase the flow of stormwater runoff and pollute the county’s already impaired streams.

“While I don’t have a strong science background I had enough understanding to know that, yeah, there are right ways and wrong ways to develop areas,” said Stone.

Stone is a moderate man and he says he is not partisan in any way. His connection to the environment, he says, stems from his childhood. Growing up on a 250-acre tobacco farm, Stone had seen first-hand as a boy how agricultural and development practices can harm the land and water.

The farm he grew up on was just outside of Orrum, a little place south of Lumberton in Robeson County. He spent summers helping his dad on the farm, pulling out tobacco from the wooden slides and stacking it on tables to be strung and dried. In the 1960s and ‘70s tobacco farming was very labor-intensive work, and his father worked round the clock. His mother worked for the railroad.

Orrum had a little country store and gas station where folks congregated to chat about politics and whatever else was going on. The Stone family attended a conservative southern Baptist church about 2.5 miles from the house.

“Everybody knew everybody else and everybody tended to everybody else’s business,” said Stone.

Until junior high his family shared a party line telephone with seven other people, and Stone would often have to wait his turn while the women shared community news and gossip.

Stone decided at an early age that he did not want to be a tobacco farmer. “When I was in the 8th grade,” he said, “I told my parents that I loved them to death but that I did not want to take over the farm, that I intended to go to college at Carolina, and that I probably would not be coming back to Robeson County.”

By the 1960s when integration reached the county, Stone had started taking notice of the segregation around him. He can close his eyes and still picture the sign in the Lumberton movie theatre lobby that read “balcony for colored.”

In Orrum where Steve Stone grew up the country store was the community gathering spot. |

“That seemed really strange to me because on farms you worked with people of other races. That’s just how it was,” said Stone. “For as long as I can remember I pretty much just thought people were people.”

Robeson County is the largest and most ethnically diverse county in North Carolina. Both Lumbee Native Americans and African Americans worked on the Stone farm.

Stone entered the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1975, and a new world opened to him. Chapel Hill broadened Stone’s views of the world and what people considered to be critical problems: “I didn’t realize how relatively wealthy Americans were until I was in college,” he said. “I started to study other cultures. The poorest Americans are still wealthier than so many hundreds of millions of people around the world. It sort of reframed my perspective.”

Stone’s mother wasn’t pleased to learn that Stone chose a black roommate his sophomore year in college. His father quickly riled when Stone came home saying things like, “Jesus was the first socialist.” He did it partly to goad his father.

The way the university facilitated education for thousands of students and faculty members was a world apart from his high school class of 96 students. “It just seemed that things around me—that collaboration was a much more effective tool than separation,” said Stone, an observation that would later shape Stone’s character and his management style.

Stone was studying recreational administration at Chapel Hill, although he discovered during his senior internship that he was more interested in what was going on in city hall then he was in the parks.

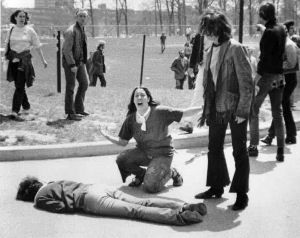

Growing up, Stone was somewhat cynical of government. As a boy he watched the Vietnam War and the Watergate hearings unfold on TV in his high school history class. The killing of four antiwar activists at Kent State University in 1970 rocked Stone.

“Even at 13 and a half [years old], I was like, ‘Why on earth would national guardsmen be shooting college students?’ That was just completely crazy to me,” he said. “And, I guess if there was a moment that changed my political perspective, it was that.”

The killing of antiwar activists at Kent State University in 1970 had a profound effect on Steve Stone. |

After getting his bachelor’s degree, Stone immediately re-enrolled at Carolina for a master’s in public administration.

He never had to leave the ninth floor of the Granville West Tower dormitory. Most of the young men who came to live on his floor stayed for many years, forming an affection like that of a brotherhood.

“With anyone’s college experience you don’t necessarily want to say the very first thing that pops in your mind,” said Kevin Brown, another small-town guy who was one of Stone’s best friends from college.

“Never met a soul that would have a bad word to say about Steve,” Brown said. “He was always responsible, always willing to lend a hand; he knew the right thing to do, and he did it.”

The group still meets for a reunion every year around a home game during the football season.

With his master’s degree nearly completed, Stone met Susan, his wife to be, in August 1984. She was a nurse at a convalescence center in Chapel Hill where Stone’s aunt was a resident. Things moved quickly. They were engaged in December and married the next spring.

The couple has nine children, including two from Susan’s previous marriage and three adopted from an orphanage in Brazil.

Outside of his home life, Stone oversees over a dozen county departments, including all those listed under the departments of Operations Services, Land and Development Services, Technology and Community Services.

“When you’re a generalist manager overseeing so many diverse areas as I do, the management has to ebb and flow. You’re not equally committed to every department at the same time,” said Stone.

Friday: Partnering with the N.C. Coastal Federation