This is part a monthly series about the food of the N.C. coast. Our Coast’s Food is about the culinary traditions and history of N.C. coast. The series covers the history of the region’s food, profiles the people who grow it and cook it, offers cooking tips — how hot should the oil be to fry fish? — and passes along some of our favorite recipes. Send along any ideas for stories you would like us to do or regional recipes you’d like to share. If there’s a story behind the recipe, we’d love to hear it.

Could the humble sweet potato pie be the fuel that fired North Carolina’s tremendous fishing industry?

The rich, spicy treat these days may pop up most often at the end of holiday meals, but in years past sweet potato pie was the start of a hard-working fisherman’s day.

Supporter Spotlight

Carteret County natives especially like to tell the “potato pie” story. On brisk mornings, oftentimes before sunrise, strong men who worked the mighty sounds and Atlantic Ocean around Carteret’s barrier islands would wake up to sweet potato pie.

John Gerard, a famous English botanist and herbalist, wrote about sweet potatoes in his massive and heavily illustrated 1597 book on herbs and plants. The lowly sweet potato had found its way to the Old World after Christopher Columbus’ voyages to the new one, where the tuber was native. |

A slice was not nearly enough sustenance for the tough labors of setting nets, raking clams or hauling fish by the hundreds of pounds to market. These men drank what amounted to soup bowls full of hot coffee with not two or even three slices of sweet potato pie.

They folded entire pies in half and ate them like breakfast sandwiches.

What today’s diners think of as dessert was true and established nourishment for those long-ago fishermen.

Ten years after Sir Walter Raleigh attempted to establish a settlement at Roanoke Island, England’s John Gerard wrote about the sweet potato in his 1597 Great Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes, in which he suggested “that the sweet potato “comforts, strengthens, and nourishes the body,” Jennifer Harbster, a librarian for the Library of Congress, wrote in her November 2010 blog “A Sweet Potato History.”

Supporter Spotlight

When Christopher Columbus discovered sweet potatoes in the New World, Peruvians had been growing the tubers for thousands of years, and sweet potatoes were well established in South and Central America, Harbster found.

“Columbus brought sweet potatoes back to Spain, introducing them to the taste buds and gardens of Europe. Europeans referred to the sweet potato as the potato, which often leads to confusion when searching for old sweet potato recipes. It wasn’t until after the 1740’s that the term sweet potato began to be used by American colonists to distinguish it from the white (Irish) potato.” Harbster wrote.

Both white and sweet potatoes thrived in gardens in coastal North Carolina and on its barrier islands where fishermen lived. Sweet potatoes flourished in the coast’s hot, moist climate and sandy soils. Growers appreciated the plant’s lack of natural enemies.

Today, North Carolina is America’s No. 1 sweet potato producer, supplying about half the U.S. supply, the N.C. Sweet Potato Commission reported.

Coastal North Carolina residents growing sweet potatoes were also familiar with sweet potato pie, a recipe handed down from their English and European ancestors.

“Sweet potatoes are ‘New World’ foods, pie is an ‘Old World’ recipe,” according to The Food Timeline history research service. “Creamy recipes combining orange vegetables with sweeteners, spice and cream were known in Medieval Europe. Carrots were sometimes employed in this manner in England.”

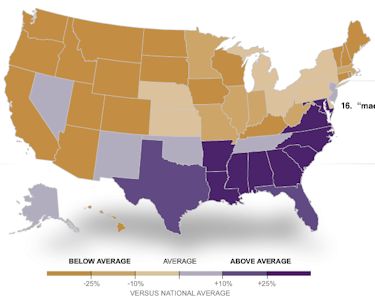

Sweet potato pie came in 15th on the top recipe searches at Allrecipes.com. It is clearly a Southern favorite. Map: N.Y. Times |

“The earliest references we find to potato pie in English cookbooks were printed in the 18th Century. They bear striking resemblance in both ingredients and method to pompion (pumpkin) pies of the 17th century.”

Early sweet potato pie recipes were included among savory listings. By the 1800s, sweet potato pie formulas were grouped with desserts, The Food Timeline reported.

North Carolina fishermen knew sweet potato pie could go either way. The pies they enjoyed were simple affairs of mashed sweet potatoes, milk, eggs and spices, providing plenty of protein from the milk and eggs and big doses of vitamin A and beta-carotene from the sweet potatoes.

No matter the recipe, cooks agree that perfect sweet potato pie is a balance of creaminess, sweetness and spices against a sturdy, savory crust. The filling is so smooth and flavorful, no ice cream or whipped cream garnish is required.

Southern journalist John Egerton, who passed this year just days before Thanksgiving, was an authority on Southern recipes and food history. His book, Southern Food (Alfred A. Knopf, 1987) is an informative and delightful collection of facts, anecdotes, stories and recipes about the South’s varied menu.

This is the recipe Egerton included for sweet potato pie. He leaves it to individual cooks to blend the spice mix to their tastes. The recipe also lets bakers choose from different milk options. N.C. coast natives would likely choose canned evaporated milk or “sweet milk” (canned sweetened condensed milk), as that is the milk their ancestors relied upon in the days when fresh milk and cream were not readily available.

Sweet Potato Pie

Prepare a 9-inch, deep-dish or 10-inch regular pie crust. Boil 3 medium-to-large, scrubbed sweet potatoes until tender, cool them and then peel and mash enough to make 3 cups. Cream 1 stick of softened butter with 1 cup of firmly packed brown sugar (light or dark), then beat 3 eggs and combine with the butter and sugar mixture. Add ¼ teaspoon of salt, ½ teaspoon vanilla extract and a combination of spices (cinnamon, cloves, ginger, nutmeg, allspice, mace) totaling 1½ teaspoons. Stir in the mashed sweet potatoes. Add 1 cup of sweet or evaporated milk or half-and-half, beat the mixture well and with an electric mixer and pour into the pie shell. Bake at 350 degrees for 50 minutes to 1 hour or until the center of the pie is firm.

— Source: “Southern Food” (Alfred A. Knopf, 1987) by John Egerton.