The Environmental Protection Agency announced earlier this year that it had adopted a new permit intended to protect U.S. waters from invasive species by imposing new regulations on ballast water released from ships. Many at the time probably thought a long legal battle was over.

The new rules, which are supposed to go into effect in December, included numeric limitations on organisms in the water that could be released from ships, and the EPA touted them as “the most stringent standards” that ballast water treatment systems can “safely, effectively, credibly and reliably meet.”

Supporter Spotlight

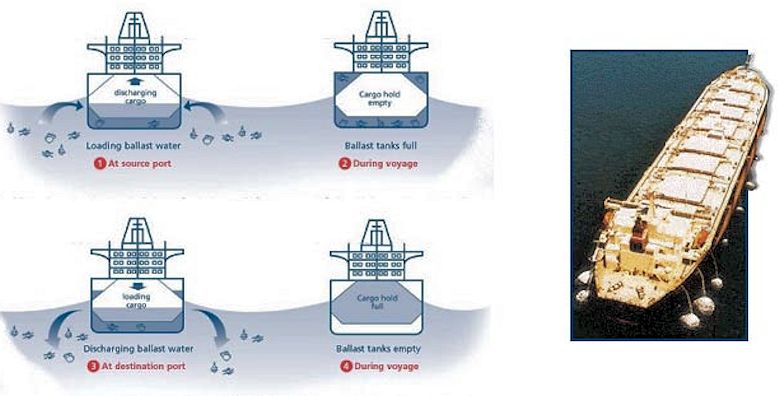

Though N.C. coastal waters don’t appear to have been affected, ballast water discharges by ships can have a negative effect on the marine environment. Cruise ships, large tankers and bulk cargo carriers use a huge amount of ballast water, which is often taken on in the coastal waters in one region after ships and discharged at the next port of call, wherever more cargo is loaded.

The ballast water contains a menagerie of aquatic organisms — minute jellyfish, larval mussels and barnacles, marine worms, tiny shrimp-like copepods and juvenile fish. These creatures share their confines with an assortment of single-celled plants and even smaller bacteria and viruses. Many of these organisms can withstand the hardships of an ocean journey and can cause extensive ecological and economic damage to aquatic ecosystems.

The ballast water contains a menagerie of aquatic organisms — minute jellyfish, larval mussels and barnacles, marine worms, tiny shrimp-like copepods and juvenile fish. These creatures share their confines with an assortment of single-celled plants and even smaller bacteria and viruses. Many of these organisms can withstand the hardships of an ocean journey and can cause extensive ecological and economic damage to aquatic ecosystems.

The U.S. shipping industry reacted quickly to the EPA announcement, but in a way some might not have expected. “EPA’s final rules now end the debate over ballast water regulation: environmental protection can now begin,” said Steve Fisher, executive director of the American Great Lakes Ports Association, said in a press release at the time. “From this point forward, ship owners will be busy making arrangements to install the necessary ballast water treatment equipment.”

Fisher reiterated that assessment in a recent interview. But the debate over the issue, which centers on the Great Lakes and at the major ports on the West and Northwest coast of the U.S., wasn’t over. While shippers might have thought the new rules were plenty tough enough, environmental groups at the forefront of the battle sure didn’t.

“The rules just aren’t good enough,” Marc Smith, senior policy analyst for the National Wildlife Federation said in an interview in June. “We don’t think they go nearly far enough to stop invasive species from entering U.S. waters.

Supporter Spotlight

Even the EPA can’t really explain how the new permits will work, Smith said. They won’t require any monitoring, he said, and contain standards that are much too high.

“The problem is that without a very low and specific standard, you don’t accomplish anything,” Smith continued. “The case of the zebra mussel in the early ‘90s in Lake Ontario is a perfect example. When they were detected, the numbers were already so high it was too late to stop the problems.”

The permit, which replaces rules that had been in place for five years, further regulates the ballast water that ships carry in their hulls to keep them balanced. The EPA said in March that the new permit set the first standards for the numbers of invasive species that can be present in ballast water before it is released. In total, standards were set for 27 kinds of discharges from commercial vessels greater than 79 feet in length. In addition, the new permit brings federal ballast water standards in line with those of many Great Lakes states and the U.S. Coast Guard. It also included new regulations mandating that ballast water treatment systems are operating correctly, the agency said.

Under the EPA permit and the Coast Guard regulations, ships built after Dec. 1 will have to comply with the treatment standards immediately. The requirements will be phased in for existing vessels over several years, with treatment technology being installed as ships are taken out of service for maintenance. The EPA contends that a faster change isn’t feasible because the manufacturers need time to produce equipment, shippers need time to install it and vessel owners have to find times to put the ships in dry dock to have the work done.

The National Wildlife Federation and other groups filed a lawsuit in July, claiming that the rules weren’t tough enough. In a press release that accompanied the court filing, the federation said that ballast water has been responsible for most of the alien invaders that have changed the Great Lakes in recent decades, causing at least $200 million in damage annually: “Zebra mussels, quagga mussels, spiny water fleas and round gobies have turned the Great Lakes ecosystem on its head, altering the food web and threatening the health of native fish and wildlife,” the federation said.

The Great Lakes are now believed to be home to more than 180 nonnative species, and dozens of them have been blamed on contaminated ship-steadying ballast water.

“This is a living pollutant that should be regulated and stopped under the Clean Water Act,” Smith said in the interview before the suit was filed. “What the government needs to do is set a high standard and let the industry find a way to meet it. We know that kind of action has worked. The shipping industry has resisted the development and use of new technologies that can do that. The shipping industry needs to work with us.”

The issue goes back at least two decades, played out both in court and in discussions in public and behind closed doors.

The EPA, according to Smith, refused for years to set rules for ballast water under the Clean Water Act, but was ordered to do so by federal courts after environmental groups sued earlier this century. The agency issued an industry-wide permit in 2008 requiring shippers to exchange their ballast water at sea or, if the tanks were empty, rinse them with salt water before entering U.S. territory in hopes of killing freshwater species inside. Environmentalists sued again, saying those requirements were inadequate.

Mike Mallin |

Pete Peterson |

Mike Orbach |

“Generally, the national maritime industry’s position has been that the U.S. ballast water regulations should be homogenized with international rules,” Fisher, a spokesman for the Great Lakes Ports Association, said in an interview just before the NWF and the other groups filed their latest court action. “Ships are obviously mobile. They’re always going from one country to another. It really doesn’t make any sense and it would be extremely problematic if there are different sets of rules in each country.”

The industry’s biggest fear, he said, was that environmental groups would push EPA to adopt aggressive rules that were unlike those in other countries. “We understand that. That’s who they are, that’s what they do,” Fisher said of the advocates. “They always push for tougher and tougher rules, and they’re not terribly concerned about homogenization.”

The industry, though, is satisfied with EPA’s new permit, he said. “What we had said is we were willing to do as much as can, given the technology that is available. No one wants to introduce exotic species that can do damage. But we didn’t want to be asked to do the impossible.”

The issue has not raised nearly as much concern or debate in North Carolina as it has elsewhere. The state’s two ports, at Wilmington and Morehead City, don’t appear to have been entry points for any significant invasive species.

Marine scientists Mike Malin at the University of North Carolina-Wilmington, Charles “Pete” Peterson at the UNC Institute of Marine Sciences in Morehead City and Mike Orbach at the Duke University Marine Laboratory in Beaufort knew of no such problems flowing from the state’s ports, nor did Steve McGhee, Prevention Department Head at U.S. Coast Guard Sector North Carolina in Wilmington.

“I’m not aware of any exotic species that have arrived in North Carolina through ballast water and caused problems,” McGhee said.

One may have found its way here from Virginia, though. Gracilaria vermiculophylla, or red algae, is indigenous to the coast of the Pacific Northwest. It easily recruits to hard substrates such as oyster and other shell material and fragmented specimens recover well and travel easily. This exotic is thought to have arrived to the U.S. East Coast near the Chesapeake Bay with Asian oysters imported into Virginia or through ballast water discharge. The algae are now considered an established invasive species along both coasts of North America and parts of central Europe. This aquatic invasive species can be found year-round in Masonboro Sound and the Cape Fear River estuary system.

Peterson said that although North Carolina doesn’t appear to have a problem, that doesn’t mean marine biologists and others should not be interested in the final rules.

“If we haven’t had any clear cases of marine invasive species from ballast water in North Carolina, the question might be why?” he said. “Clearly, we don’t have the same level of international shipping as the Great Lakes and the some of the other ports, such as on the West Coast, but we do have international shipping. We do have the risk.”

Malin said one factor might be the frequency of relatively low salinity levels at the Wilmington port. On the other hand, he said, there surely is some degree of just plain “good luck” involved.

Orbach, the Duke Marine Lab professor and researcher, comes at the concept from a different perspective. He’s a professor of marine affairs and policy, with degrees in economics and cultural anthropology, and thus might focus more on the people part of the marine equation. Although he’s an ardent conservationist, as well as a fisherman, surfer and sailor, he wonders how far rules need to go.

“I have to say, I do have a problem getting too ‘exercised’ about this as a major issue, in general,” he said. “There are obviously some bad cases, such as the zebra mussels in the Great Lakes. But we do live in a modern world and shipping is a big part of that. You want to do all you can, but you have to be practical.”

McGhee said the Coast Guard, not state ports, would have the responsibility to enforce the EPA rules, a fact also cited by N.C. Ports Authority spokesman Laura Blair when she declined to comment for this story.

McGhee said that while the rules do phase in requirements for some vessels to have onboard ballast water treatment systems, the Coast Guard’s role under the rules would still be largely administrative.

“We don’t ‘check’ ballast water,” he said. “We make sure that the ships’ paperwork shows that they are complying with the rules. There will be thresholds, and when they are required to install equipment, they will have to submit the designs to us for approval. Essentially, we will be making sure that everything is working as it is supposed to work, and that they are using Coast Guard-approved systems.