NAGS HEAD — By now, most people along the coast of North Carolina can see for themselves that the sea is rising. Pine trees in estuarine marshes are dying from saltwater intrusion; ground water levels seem higher; beach erosion has worsened.

The tough message Michael Orbach, a Duke University marine science professor, had recently for an Outer Banks audience: Get used to it.

Supporter Spotlight

There is nothing that humans can or will likely do between now and 2100 that will significantly slow the rate of sea level rise, he said at a presentation last week at Jockey’s Ridge State Park, sponsored by the League of Women Voters of Dare County.

“The implication there is we can’t avoid it, so we’re going to have to adapt to it,” said Orbach, a former director of Duke’s Marine Lab in Beaufort.

Slide after slide of graphs, maps, photographs and charts in his presentation showed consistent evidence that with the start of industrial revolution in the 1800s, levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide, global temperatures and the seas all started rising.

And as air gets warmer, Orbach said, the ocean gets warmer. Water heats up slowly, but once it does, “it’s going to stay warm for a long time,” slowing currents and altering weather patterns.

Sea level projections, he said, are based not just on computer models , which skeptics perceive to be subjective, but also on actual readings from at least 1,000 tide gauges starting from 1900 and core samples from glaciers.

Supporter Spotlight

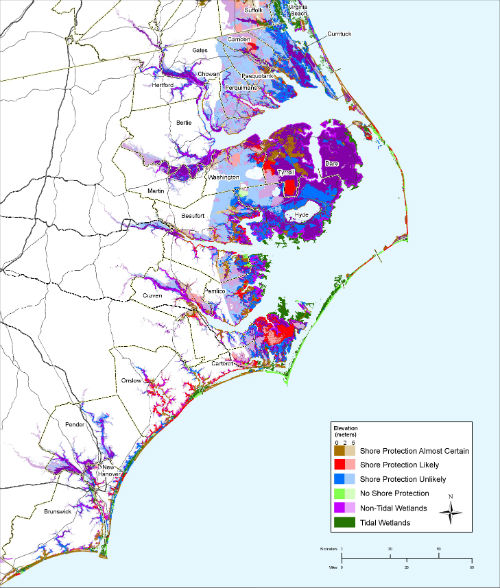

Likelihood of Shore Protection:A $2 million effort maps the likelihood of shore protection along the East Coast as sea level rises. The maps divide coastal low lands into four categories: developed (shore protection almost certain), intermediate (shore protection likely), undeveloped (shore protection unlikely) and conservation (no shore protection). The North Carolina portion of the study was led by North Carolina Seagrant. For further details, see the report on the summary of North Carolina findings. |

“Every year we get more data,” he said, “the estimate goes up.”

Over the past 500 million years, global sea level has gone up and down by hundreds of meters, Orbach said. The average sea-level rise worldwide over the last 100 years has been one foot, he said, but the projection for the next century is at least one meter, or 39 inches.It will not be easily reversed, Orbach noted said.

“This is the important thing about sea level rise — it’s a permanent state,” Orbach said. “For the next several thousand years, it’s only going to go up.”

Still, Orbach said there are a multitude of reasons to decrease use of carbon-based fuels like oil and coal, including clean air and energy independence.

With its long coastline and huge low-lying estuarine system, North Carolina is going to see wide-ranging affects from rising seas, especially along the low-lying Outer Banks, he told the audience of about 60 people.

And it will be more evident on the sound side than along the oceanfront. Storm surges from even small storms will be more destructive; tides will be higher; increased erosion will require more engineered solutions.

Septic systems will be the first casualty of higher ground water levels and eroded waterfronts.

After becoming the butt of jokes for passing a law last year that required sea-level rise rates to be based on historical trends dating back from 1900, and not to include data on accelerated rates, North Carolina legislators eventually reached a compromise to refrain from passing new sea-level regulations until 2016. Meanwhile, the best available science will continue to be gathered.

“The Europeans think we’re a riot,” Orbach said later in an interview. Other countries — Germany, for instance, is planning 500 years out for climate change impacts — are actively seeking ways to cope with future sea-level rise.

Partisan politics here has hampered any reasonable approach to the issue, he said.

“The U.S. House of Representatives is a truly silly place right now,” he said. “They will not even look at — no less fund — anything that has the words ‘climate change’ in it.”

Despite the intransigence, a national climate assessment, mandated, but never funded, by Congress in 1990 is expected to be released in April. Universities and private researchers had to do pay for much of the work.

Even with the United States lagging on the global stage in its climate policies, North Carolina is behind other coastal states, like Maryland, New Jersey and New York, which have implemented state policies to cope with rising seas.

Michael Orbach |

A 2012 study by the U.S. Geological Survey said that seas along the Atlantic coast from North Carolina to Massachusetts are rising three to four times faster than the global average. The Outer Banks, New Orleans and the Florida Everglades, all at or below sea level, are the most vulnerable areas in the nation.

Some developers and real-estate brokers in North Carolina have questioned the validity of the sea- level science. They also said that creating policy based on a projected one-meter rise would hurt economic development. Orbach said he understands the concern of skeptics, although it doesn’t change the reality.

“The problem is that the effects at some point will be so great, they’re afraid,” he said. “They don’t know what to do. And so there’s a tendency to say ‘Maybe it’s not true.’ I think part of it is fear of economic loss and economic turmoil.”

If he were a planner on the Outer Banks, Orbach said, the first thing he would do is map the area and calculate the effects of sea-level rise up to three feet, similar to what his Duke student Jeffrey Allenby did for the Bogue Banks in his 2011 master’s project. Allenby used GIS data to model the effects of sea-level rise on the sound and ocean sides of the island.

As described in the paper’s abstract, the maps could assist development of new regulations.

“In particular, policies pertaining to the issues of migrating wetlands, septic tank permitting, zoning of buildings and transportation will likely need to be reconsidered if towns are going to successfully adapt to and mitigate the effects of higher sea levels,” Allenby wrote

His maps, which were part of Orbach’s presentation, showed areas of Pine Knoll Shores and Atlantic Beach completely inundated with spring tides or continually submerged at mean high tide.

With the projections, planning for infrastructure and roads could work around future conditions in a proactive manner, Orbach noted. Regulatory solutions include setbacks, rolling easements —allowing structures to move back from the water — conservation easements and buyouts, where threatened properties are purchased by the government and removed.

“The problem is, if we don’t start planning for it, everything is going to be so much worse when it does start happening,” he said.

Planning, Orbach said, could keep future growth away from vulnerable areas, strengthen building codes and design and consider the effects of future sea-level rise before issuing plat approval or road elevation variances.

The legal system, he said, also has to adapt to “become trusting of these future judgments.” As it is now, if a planning board rejected an application because of projected sea-level rise, most likely the applicant could sue in court and win, Orbach said.

Ideally, the entire estuarine and ocean shoreline in the state should be mapped,he advised. Once the mindset changes to accepting the permanence of high water, it won’t be as difficult to deal with it.

“Think of it as storm surge that doesn’t go away,” he said. “The good thing is, because it’s a little off in the future, there’s time to plan.”

For instance: What will a community do with the existing infrastructure? Where will it put all of the stuff it wants to keep? Should construction of infrastructure be stopped in increasingly vulnerable areas?

Through the ages, Orbach said, history has shown what people do when conditions become too difficult to live: They move somewhere else.

“The good news is,” he said sardonically to the audience of mostly middle aged or older folks, “you don’t have to worry about it too much.”

That may be what is contributing to the slow pace of government response.

“Beyond current political cycles, there’s very little incentive for politicians to do anything about it now,” he said, “because they’re not going to be here either.”