While known for usually wearing her hair piled on her head in a loose bun, often with glasses and pens stuck in the mix, Carolista Fletcher Baum is captured here with her hair down, in front of the sand dune she helped save. Photo: Outer Banks History Center; photographer, Drew Wilson |

NAGS HEAD — One summer day 40 years ago, Carolista Fletcher Baum stood firmly in front of the lead bulldozer threatening to flatten the East Coast’s tallest sand dune until the operator turned it off and left.

That night, she returned and removed the distributor and rotor caps and key locks from the fleet of bulldozers, according to later accounts, single-handedly kicking preservation efforts into high gear.

Supporter Spotlight

Her action sparked a statewide movement that led to the creation of Jockey’s Ridge State Park two years later. Baum provided the spark and was the movement’s recognized leader, but many others helped along the way.

“We pulled it off,” said Marlene Roberts Brantley, who was involved from the beginning with the nonprofit People to Preserve Jockey’s Ridge that Baum started. “Everybody played a part.”

Edward Greene, owner of The Christmas Shop in Manteo, dove wholeheartedly into the effort after seeing a newspaper picture of Baum’s audacity and learning of the circumstances, he said. Like many locals at the time, he had not realized that the land was privately owned and under threat of development.

“She was not a large person—and she was standing in front of the bulldozer giving the impression ‘I’m not moving,’” Greene recalled.

“In all probability there would be no Jockey’s Ridge State Park today if it had not been for Carolista Fletcher Baum and her husband, Walter,” the late David Stick wrote in his historical account People to Preserve Jockey’s Ridge, 1973-1980.

Supporter Spotlight

But they hadn’t been the first to try.

Marlene Roberts Brantley |

Edward Greene |

When he was elected president of the Nags Head Chamber of Commerce in 1964, Stick tried to make Jockey’s Ridge public domain. He “failed miserably,” he wrote, because the landowners were “reluctant to even discuss the idea of selling their Jockey’s Ridge interests at the time when Nags Head real estate was finally booming.”

In the winter of 1971-72, developer John High of Rocky Mount sought the Nags Head Planning Board’s approval to build condominiums on the northwest edge of Jockey’s Ridge, Stick chronicled.

Photojournalist Henry Applewhite and real estate broker Philip Quidley published an article in The Coastland Times about the proposed development. Soon after, Stick received a telegram from their loosely organized “Friends of Jockey’s Ridge,” requesting help in preventing the dunes’ destruction.

The Friends convinced the N.C. Division of State Parks to send out a representative. But there was no money to buy the land, and the group dissipated.

“Percy Meekins owned the property, so we were in conflict with him,” Greene remembered. “Rather than building development around the foot of Jockey’s Ridge, we decided it needed to be saved for future generations. We decided we needed to get petitions together and appeal to the state.”

Baum served as president of People to Preserve Jockey’s Ridge. Luther Hodges, a former governor, was first vice-president. Greene and Brantley were the other officers. Walter Baum, Stick and Nags Head Mayor Carl Nunemaker were also part of the 15-member board of directors.

“She was a good front person,” Brantley said of Baum. “Walter Baum was kind of the quiet hand behind the scenes. He probably has never really gotten proper credit for what he did.”

“David was extremely helpful”, she continued. “He knew everybody in the state, federal level.”

Brantley said she was a fulltime, unpaid employee of the organization that first year, putting in about 40 hours a week.

She returned to work in 1974 but she and Baum, an accomplished jeweler who owned stores in Nags Head and Chapel Hill, spent every weeknight working on the project.

“By then we had coin canisters in a lot of businesses; we were getting donations, counting coins,” Brantley recalled. “The five children—my two and her three—got along very well.”

The children were regular, albeit sometimes reluctant, volunteers.

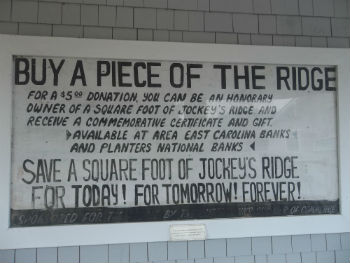

On the back outside wall of the visitor center at Jockey’s Ridge State Park, an original 1970s sign is displayed. The bottom line reads “Sponsored for the People by the Outer Banks Chamber of Commerce.” Photo: Corinne Saunders |

The group sold “SOS”—“Save Our Sand Dune”—T-shirts and bumper stickers, plus $5 certificates to “own” a square foot of Jockey’s Ridge.

“Why can’t we just play on the dunes?” Ann-Cabell Baum Andersen, the eldest of Baum’s children, recalled wondering as she and her sister Inglis and brother Gibbs headed to the hot watermelon-pink hut that was the center of their fundraising and petition-signing recruitment efforts.

“Everyone who lived in Nags Head or on the Outer Banks knew that hut,” she said with a laugh, explaining it was painted with leftover paint from their bathroom in Chapel Hill.

“We didn’t know not every mom would take up a cause and fight for it just because that was the right thing to do,” Andersen noted.

The granddaughter of novelist Inglis Fletcher, Baum grew up in a prominent family in Edenton and spent every summer of her life in Nags Head. She was a statuesque woman known for her beauty, charm and flair, with a raspy voice and warm, brown eyes. “My mom was hot pink, fuchsia, purple, bright blue,” Andersen told a magazine writer once. “Not white.”

She was also determined. When Baum severed her right two middle fingers making jewelry, she taught herself to write letters left-handed. When Ann-Cabell developed pneumonia, Baum’s phone calls and letters continued from her daughter’s bedside. The sand dune, it turned out, had consumed her, as it had a motel and several houses foolishly built in its path over the decades.

Newspaper reporters notice such things. They wrote admiring stories of the lady who was pestering everyone in the state to save a sand dune. Of course, those stories only helped the cause.

The Christmas Shop was another headquarters. Greene made announcements over his PA system, and local attorney Leonard Logan’s daughter and Brantley’s son manned an SOS booth outside the store.

The money generated went to buy stationary and stamps for the writing campaign, Greene said.

Jockey’s Ridge placemats were printed and sold to restaurants, and colored screen prints were sold in gift shops.

“We had a full Dare County campaign going,” Greene said.

Named for the woman who stopped the bulldozers, W Carolista Drive is the entrance street to Jockey’s Ridge State Park. Photo: Corinne Saunders |

Stick noted, however, that even though spirits were high because of people’s widespread support, the money generated fell far short of what was needed to buy the land, making the state’s involvement vital.

The nonprofit sent petitions with more than 50,000 signatures to Raleigh, along with countless other pages of correspondence. Baum drove to the capital every day for three weeks straight, speaking with every legislator she could buttonhole. She persuaded songwriters to sing about Jockey’s Ridge and invited filmmakers to the dunes. Her efforts even motivated poet Carl Sandburg. “Save the dunes,” he said. “They belong to the people. They represent the signature of time and eternity. Their loss would be irrevocable.”

The N.C. General Assembly finally listened, appropriating the money to buy the first 152 acres in 1975. Along with land donations and other purchases, the park would soon total its current 426 acres.

Later that summer Ann-Cabell and her siblings stole out of the house at sunrise one day and trudged to top of the highest ridge. There, they triumphantly tromped around, dragging their feet through the sand in organized lines. They returned home and woke their mother. Baum walked to the door and saw a message drawn in the dunes that she helped save. “Happy Birthday, Mom.”

She died in 1991. The park she helped make remains and has become the most-visited state park in North Carolina.

“It was the smallest park the state had ever created, period; but it was extremely timely and, you know, we needed it, so it worked,” Brantley said. “Because of all the development, it doesn’t get as much sand and re-nourishment as it used to, but it’s still there.”