CHATHAM, Va. — A state legislative commission, in a letter to Virginia’s governor, expresses “significant concern” about the possible adverse effects uranium mining in Virginia will have on rivers and lakes in northeastern North Carolina.

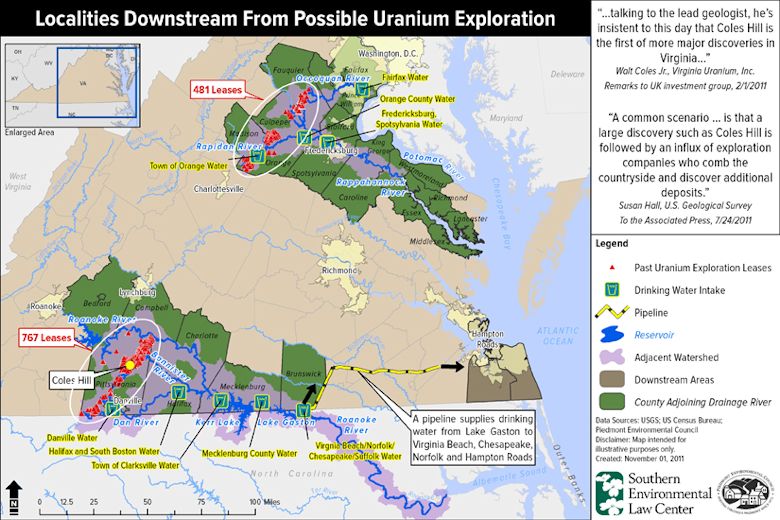

The letter that the state Environmental Review Commission voted yesterday to send to Gov. Bob McDonnell is the first official state reaction to Virginia’s proposal to lift a 30-year ban on uranium mining at a huge deposit of the radioactive ore on Coles Hill in southeastern Virginia. The mining site is in the Roanoke River basin. The river, a drinking water source for more than 100,000 North Carolinians, flows south into Albemarle Sound.

Supporter Spotlight

“At its December 13, 2012 meeting, the Commission expressed significant concern regarding the potential lifting of the existing legislative moratorium on uranium mining in Virginia,” the letter to McDonnell notes. “The Commission requests that you consider the possible adverse impacts to Kerr Lake, Lake Gaston and many communities in northeastern North Carolina if the existing legislative moratorium on uranium mining is lifted and mining activities commence…”

The commission also asked Gov-Elect Pat McCrory to meet with McDonnell to discuss North Carolina’s concerns.

The Virginia legislature is expected to take up the issue when it convenes next month.

It makes sense for North Carolina to get more actively involved, said Ryke Longest, the director of the Duke University School of Law’s Environmental Law and Policy Clinic.

Ryke Longest |

“The state of North Carolina would be foolish not to challenge actions by Virginia that threaten water resources of both states,” he said,

Supporter Spotlight

Longest said that the law clinic is representing the Roanoke River Basin Association in evaluating a response to the mining proposal. Unlike other U.S uranium mines, which are in arid locations, he said, the site Virginia is considering in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains is vulnerable to intense storms and heavy rainfall.

“This is a particularly dangerous spot,” Longest said.

A 104-page report issued on Nov. 30 to McDonnell by the Uranium Working Group, an ad-hoc group he appointed in January, offered little comfort to uranium mining opponents in both states.

“There are no assurances or reclamation plans, or provisions for damages for anyone in North Carolina in the VA. governors’ working group draft regulations,” Mike Pucci, chairman of the N.C. Coalition Against Uranium Mining, said in an e-mail. “In fact, North Carolina was not even consulted during the process or invited to participate. The Virginia governor will now hand this nuclear time bomb off to the energy commission to push it through to the General Assembly for a vote.”

A meeting was held Tuesday in Chatham to hear a presentation about the report from the General Assembly’s Coal and Energy Commission. Members of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission were also on hand to answer questions, said Andrew Lester, executive director of the Roanoke River Basin Association.

Numerous questions concerned the uranium tailings, the waste product of uranium cake processing, Lester, who attended the meeting, said in an interview. The tailings, which would be stored onsite, contain a substantial level of radioactivity that studies say could contaminate local waters.

“I asked ‘Can you tell me anywhere in the U.S. where there’s a uranium mine or mill operation located in the midst of a major river system with one million or more people downstream?,’” he said. “And the answer was ‘No.’”

A statement from the association released after the meeting said that the report failed to mention the threats posed by severe weather, terrorism, thousands of years of required monitoring, maintenance costs or the effects on downstream communities in the Roanoke watershed and the quality and quantity of its water.

“No one can predict whether promised benefits of uranium mining would materialize, as no one can predict where the price of uranium is going to be in 10 to 40 years from now,” the statement said. “But what is certain here is that the radioactive waste resulting from the proposed operations will remain here in Virginia forever.”

Lester said the uranium deposit stretches all the way to Washington.

“So if the Coles Hill area is mined in the state,” he said, “that area can be mined, too.”

Uranium has so far been found in two areas of Virginia. The Coles Hill discovery in Pittsylvania County is in the Roanoke River watershed. More than a million people depend on the rivers and its reservoirs for drinking water.

An informal delegation that includes state Rep. Michael Wray, a Democrat whose new district includes Northhampton and Halifax counties, plans to meet with McDonnell on Friday to discuss concerns about lifting Virginia’s uranium mining ban.

“There’s still a lot that’s unforeseen,” Wray said in an interview. “I think the proposal is detrimental to North Carolina and our watershed.”

>

Wray, who has served in the N.C. House for eight years, is a member of the Roanoke River Basin Bi-State Commission, which opposes the mining.

“Of course,” Wray said, “our issue is we have one of the cleanest river basins there is.”

One of the largest deposits of uranium in the world was discovered in 1978 at Coles Hill, near Chatham in Pittsylvania County. In 1982, Virginia put a temporary moratorium on the uranium mining until legislators pass a law that allows a regulatory program to be put in place.

Virginia Uranium Inc., responding to an improved uranium market, became actively interested in the site in 2007. The company said that a study shows that the site will support 1,000 jobs, provide $112 million in local and state tax revenue, and generate $5 billion for Virginia businesses.

But opponents said that Coles Hill averages 42 inches of rain annually, and is subject to powerful storms and earthquakes.

Numerous studies requested by the Basin Association over the years prove that a uranium mine in Roanoke River watershed could be disastrous to the river basin, according to a July presentation to the commission by Olga Kolotushkina, the basin’s legislative and regulatory advisor.

“The common denominator — risks are high,” she said in the presentation, “and consequences are unpredictable, mainly due to Virginia’s climate.”

Rep. Michael Wray |

An article published on Nov. 19 by the Natural Resources News Service said that 19 lobbyists have been employed by Virginia Uranium to lobby state officials. One lobbyist, the article said, told Virginia business leaders at a closed meeting in October that the company was drafting legislation that would authorize state agencies to create regulations, sidestepping the need to vote directly on the project.

Kolotushkina said that Virginia’s ban cannot be lifted without passing a bill to establish a regulatory program. Once the regulatory authority is granted, the ban will automatically be lifted. But she said that the state regulators’ role may be misunderstood.

“The regulators are there to promote the industry so that it can exist,” she said in an interview. “In this country, the public interest is defined as the business interest. In practice, it’s not true. We’re not dealing with mom ‘n’ pop shops . . . As far as top management is concerned, they’re kings and queens.”

In a Dec. 5 press release, Virginia Energy Resources, Inc., owner of Virginia Uranium, applauded the state report, saying it “leaves no doubt that the state’s regulatory agencies are capable of effectively and safely regulating uranium mining.”

“The environmental performance of the uranium mining industry over the last 30 years proves that we can undertake the Coles Hill uranium project safely and in a way that protects our environment,” the statement said. “The company’s commitment is to continue this outstanding track record and operate one of the safest uranium mines in the world and in Virginia.”

Lester said that once the lame duck legislature and governor are replaced in January, he believes that North Carolina will be more responsive to the threat in their backyard.

“Everybody I’ve talked to in North Carolina, when they hear about this,” he said, “they think it’s a bad idea.”