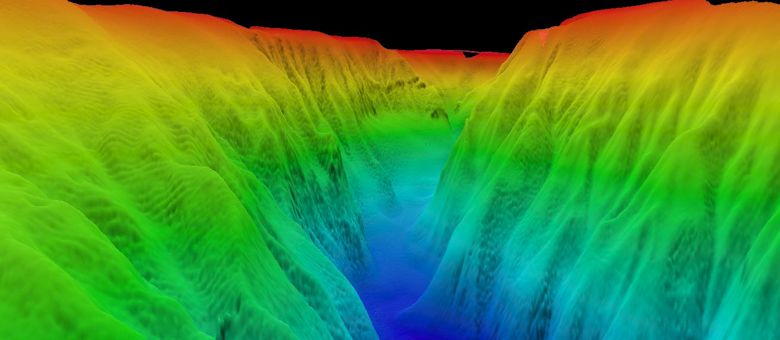

A 3-D image looking up the Baltimore Canyon, which is one of the larger submarine canyons along the East Coast. With a typical V-shaped cross-section, it cuts 17 kilometers into the continental shelf and is 700 meters deep and 8 kilometers wide at the shelf break. Photo: Atlantic Deepwater Canyon Expedition.

WILMINGTON — With more than 70 percent of the Earth’s surface covered in ocean waters, it’s little wonder that some scientists have dubbed it Planet Ocean.

Supporter Spotlight

Yet, the oceans’ depths remain a vast wilderness of mountains, canyons, plateaus, creatures and untapped resources that scientists are just beginning to discover and describe. In fact, it’s estimated that only about one percent of this deep frontier has been explored.

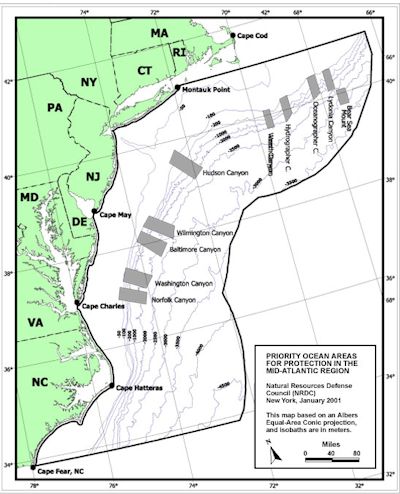

Nine submarine canyons cut into the continental shelf from Cape Hatteras to the Gulf of Maine. Map: Natural Resources Defense Council. |

But Steve Ross from the University of North Carolina Wilmington and Sandra Brooke from the Oregon Institute of Marine Biology and Marine Conservation Institute are nudging that one percent up a notch.

Ross and Brooke are leading an ambitious, four-year project to unlock the mysteries within and adjacent to the Atlantic’s Baltimore and Norfolk deepwater canyons off the coasts of Maryland and Virginia.

The objectives include locating cold seeps and vulnerable habitat, describing the canyons, investigating the biology and ecology of different types of seafloor communities and identifying archeological sites – including shipwrecks.

To meet these multiple objectives, they assembled an international multidisciplinary team of marine scientists and technicians to explore and document unique habitats and inhabitants – work that will help guide future uses and/or protection of these ocean resources.

Supporter Spotlight

Just two years into the project, Ross and Brooke describe preliminary results as “productive” and “remarkable.”

Among the findings from the 2012 research cruise: the “rediscovery” of a methane cold seep first encountered 30 years ago; the first documentation of the presence of Lophelia pertusa, a deepwater coral, in Baltimore Canyon; the discovery of a possible new species of mussel; and, the documentation of World War I German warships sunk by Gen. Billy Mitchell’s mission to demonstrate air power.

Ocean research is costly and partnerships help stretch limited research dollars. The deepwater canyon exploration is funded by the U.S. Department of Interior’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management and the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration’s Office of Ocean Exploration and Research. The NOAA ship, The Nancy Foster, is providing a platform for operations at sea.

In addition, the project is supported by contributions of both personnel and equipment from the U.S. Geologic Survey and partners from several institutions and agencies from the U.S. and Europe.

Mapping a Work Plan

Mike Rhodes, right, pours while Steve Ross holds the filter bag, purifying Gulf Stream water for coral physiology work. Photo: Atlantic Deepwater Canyon Expedition. |

Ross and Brooke launched the first phase of the Atlantic Deepwater Canyon Exploration Project in 2011, producing high-resolution maps of the seafloor of the targeted research areas.

Those maps guided the 2012 research cruise that ran from Aug. 15 to Sept. 30.

The cruise was divided into three legs. The first two concentrated on natural ecosystems and habitats found within and around the canyons, while the final leg examined historical shipwrecks and their biological communities.

The mission is being carefully orchestrated. Ross and Brooke reconfigured each research crew to match the scientific objective of each of the first two legs. Rod Mather, an archeologist from the University of Rhode Island, supervised the third leg.

To maximize valuable ship time, the researchers conducted round-the-clock operations. In daylight hours, they deployed Kraken II, a remotely controlled vehicle, or ROV, to survey habitat, biological communities and canyon characteristics.

Ross describes the canyons as “extremely rugged and as awesome and grand as the well-known Grand Canyon. They can be miles wide and in the scale of land canyons,” he says.

The ROV also was employed during the final leg’s daytime operations. Video images are being analyzed to determine the type, mission and ownership of the ships. If eligible, the shipwrecks could be nominated for the National Register of Historic Places.

The shipwrecks also are being assessed for their value as “artificial habitat” for a variety of fishes and invertebrates – not surprising considering the fact Mather’s team documented an aggregation of spawning catsharks at one of the wreck sites.

Night crews launched equipment to take core samples from the seafloor and from incremental heights of canyon walls. Crews also used small trawls to collect fauna and sediments. Water samples from various depths also were collected during night shifts.

“We also maximized our sampling efforts as well,” Brooke points out. “For example, one sample of bubble gum coral could be snipped into a dozen slices for different analyses – reproductive, genetic, isotopic, paleo, and so forth.”

The plethora of samples – from fish to water to corals – are being analyzed in laboratories of participating marine researchers from across the country from Oregon to Connecticut and Louisiana, as well as Ireland and the Netherlands.

More to Come

Goosefish, also called a monkfish, are common in Baltimore Canyon. Photo: Eric Hanneman, Atlantic Deepwater Canyon Expedition. |

A cusk enjoys his home under a bed of cold seep mussels in the Baltimore Canyon. Photo: Atlantic Deepwater Canyon Expedition. |

Lophelia was found in the Baltimore Canyon, the first time the coral had been seen in the mid-Atlantic. Photo: Atlantic Deepwater Canyon Expedition. |

Sampling from the 2012 research cruise is ongoing, thanks to the deployment of benthic landers and sediment trap moorings placed at the head, middle and base of the Norfolk and Baltimore canyons. The high tech gear is now hard at work collecting data on temperature, salinity, oxygen, chlorophyll, currents and monthly sediment deposition.

The landers are also equipped with settlement plates to assess recruitment and colonization rates of benthic fauna and experiments to measure growth and survival of deepwater corals.

The scientists will retrieve the landers and sediment moorings when they return to sea for the 2013 research cruise.

Ross and Brooke agree that it’s hard to stay professionally cool when you are part of research team documenting “firsts,” such as sighting Lophelia in the Baltimore Canyon. The deepwater coral is well documented in the Gulf of Mexico, the South Atlantic and the Atlantic waters off of the New England coast. But, there had been no observations in the Mid-Atlantic waters.

“The discovery filled a gap in our knowledge of the distribution of this important coral species,” says Brooke, who has studied deepwater corals for more than a decade.

It also was exciting to “rediscover” the Baltimore Canyon methane cold seep that was first discovered more than three decades ago by Barbara Hecker, a lead scientist exploring the Baltimore Canyon.

“She was using a towed camera to survey the seafloor,” Brooke says.

When Hecker processed the film later, she spotted images of mussel beds – indicative of a methane cold seep.

Hecker was using very old technology that produced unreliable sea coordinate readings, so her 1980’s description gave Ross and Brooke only a “sort of” location.

However, going by Hecker’s more reliable depth sensor records, they had starting point for navigating the ROV dives over transects around the approximate coordinates and known depths.

“We began to see carbonate and thick batches of mussels and thought we might be on to something,” Ross says.

Methane seeps are of special interest because they are a possible indication of the presence of oil.

“Oceans run the planet – they provide our food; steer our weather; support our commerce; and drive Earth’s water cycle. It’s the largest ecosystem on the planet. Yet, we don’t know much about what makes it tick,” says Ross, who has been studying the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico deep sea environments for about three decades.

The researchers say it’s important to protect the oceans’ resources for the long term good of humankind.