Wild Turkey FactsAverage Size Height: 3-4 ft. Supporter SpotlightWingspread: 4-5 ft. Weight: Female 10 lbs; male 17.5 lbs. Food Seeds, grasses, acorns, nuts, berries, insects. Breeding Supporter SpotlightMales are called gobblers or toms; females are called hens. Males attract females by gobbling and strutting. Wild turkeys lay eggs beginning in April. Average clutch size is about 8–15 eggs. Average of one clutch per year, but females will re-nest if the first clutch fails. Young are sexually mature in one year. Young Very young turkeys are called poults. Juvenile females are called jennies; juvenile males are jakes. Life Expectancy Two years, although some birds have lived up to 10 years. |

Back in the 1980s, people on the N.C. coast rarely saw wild turkeys alongside roadways and in fields. In fact, the bird was quite scarce all over the Tar Heel State.

But by 2005, wild turkeys were flourishing across North Carolina and continue to proliferate today. Now it’s very common to see flocks of them in rural parts of eastern counties or even a few in more urban settings from time to time, including one photographed along a median near Target in Wilmington last year. The N.C. Coastal Federation’s Sam Bland routinely takes pictures of them grazing along the roads of Carteret County.

Numbers from the National Wild Turkey Federation show that the population growth is nationwide: 1 million in 1973 vs. 7-8 million today.

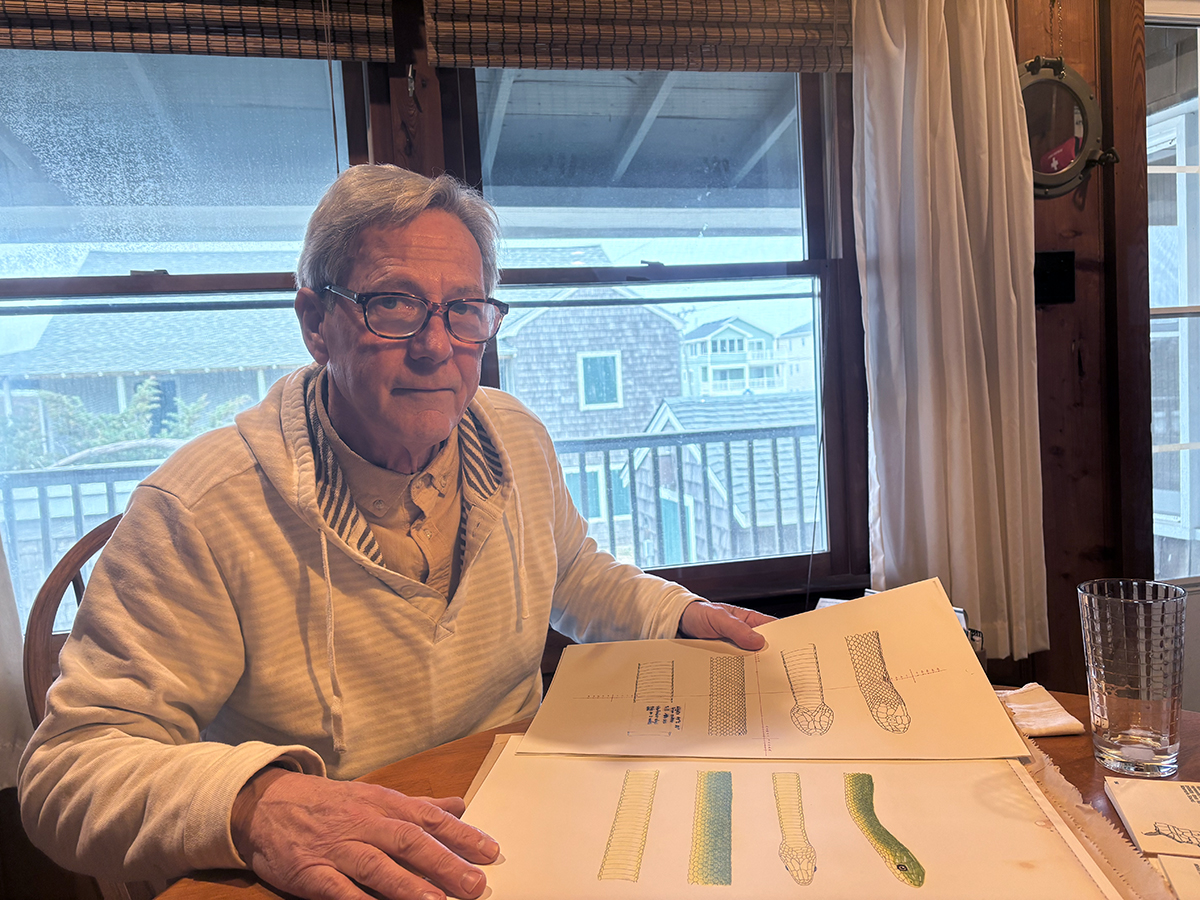

Bryan Perry |

“Everyone talks about the good-old days,” said Bryan Perry, president of the federation’s N.C. chapter. “For turkeys these are the good-old days. There are more turkeys then there have ever been, including when the settlers were here.”

This didn’t happen by accident, however, but was rather the result of a 16-year plan that involved collaboration among agencies and many other states.

“It’s arguably the greatest conservation story ever,” said Zac Morton, the federation’s N.C. regional director. “It’s what brought the turkeys back.”

He’s referring to a restoration program that started here in 1989. The concept was simply to move turkeys from locations where they were abundant to those where they were scarce or absent. From 1989 to 2000, North Carolina brought in 1,743 birds from nine states at a cost of about $900,000, Morton said. Most of the money came from the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission, with about $300,000 from the federation’s state chapter, which raises money through private donations at fund-raising events. In addition, the state received 150 wild turkeys from West Virginia in a trade for 100 river otters.

The N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission had been working to replenish the wild turkey population with in-state trapping efforts since 1953 but “things really went into warp speed” when the federation got involved, said Robbie Norville, a coastal supervising wildlife biologist with the state agency.

“Turkey numbers had dwindled to the point that there were just a few isolated populations in North Carolina,” he said. “They were almost done on the coast.”

A flock of hens surround a tom in a field near Cape Carteret in Carteret County. Photo: Sam Bland.

The decline, which started around 1900 and continued into the 1960s, was primarily due to unregulated and heavy market hunting, rapid deforestation and habitat destruction throughout the state, according to the wildlife commission.

The state agency reports that 6,031 wild turkeys have been released on 358 restoration sites across the state since 1953. About three-fourths of these birds, or 4,443, were relocated just since 1990. The state’s wild turkey population has increased from an estimated 2,000 birds in 1970 to an estimated 260,000 in 2010. Restoration efforts wrapped up in 2005.

Wild turkeys now exist in all of North Carolina’s 100 counties, and they all have a spring gobbler season.

“We’re in wonderful shape,” said Norville, who recently saw a flock of at least 70 wild turkeys in Craven County. “Birds are showing up everywhere. Hunters are commenting to me all the time that they’re just seeing turkeys everywhere. We really don’t have a county here on the coast that doesn’t have a good flock of birds.”

Many hunters seek out wild turkeys just for sport, he said. “It’s real hunting, if you will,” Norville said. “It involves scouting and calling to the birds either with your voice by yelping or with devices. They are a very vocal animal, and since they are a flock bird they do ‘talk’ to each other.”

But many wild turkey hunters like to prepare and eat their catch, which has a “very rich flavor” and “tastes like a turkey should taste,” he added.

A tom struts his stuff. Photo: Sam Bland. |

While coastal areas are teeming with wild turkeys nowadays, don’t expect to see them wading in the surf down at the beach, Morton said.

“Never say never, but there’s not much for a turkey to eat in the sand and they’re not going to drink the salt water,” he said. “You see them more in the spring in the fields during mating season. The male turkey is fanned out looking for females, and they do this in fields so they have more room.”

While they’re not into catching waves, there have been reports of seeing wild turkeys along wooded areas not far from the ocean in Carolina Beach and Emerald Isle.

“The turkey is an extremely adaptable animal, and that’s why the project has been so successful, “ Morton said. “Basically turkeys can survive almost anywhere.”

The male eastern wild turkey has dark plumage with bronze, copper and green iridescent colors. On the inside of their legs, males have pointed growths known as spurs that they use when battling other males for mates. They average about 20 pounds.

Males also have a growth of bristle-like feathers known as the beard that extends from the chest. It is not uncommon, however, to find females with a beard. The head and neck of adult males are largely bare and vary in color from red to blue to white, depending on the bird’s mood. Females, which weigh about 10 pounds, are usually duller in color than males, which helps camouflage them while they are nesting.

The eastern wild turkey, or Meleagris gallopavo, thrives best in areas with a mix of forested and open land habitats. Forested areas are used for cover, foraging and for roosting in trees at night. Open land areas are used for foraging, mating and brood rearing.

While North Carolina is in its wild turkey heyday, many other states in the Southeast are starting to see declines again, some as much as 75 percent. A task force created in 2010 and researchers at the University of Georgia are working to identify the reasons and mitigate the impact.

“It’s more than a fluke because there are too many states seeing it,” Perry said. “We haven’t seen it here yet, but once people started seeing turkeys everywhere we all got kind of somewhat complacent. There’s still work to be done to make sure what we have is going to stay.”