Reprinted from the Tideland News

First of two parts

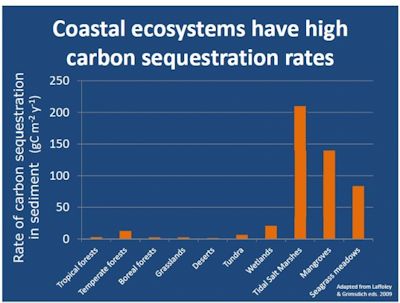

The chart shows the value of coastal ecosystems carbon sinks versus terrestrial forests and other types of habitat. Source: Cifuentes & Kauffman |

As National Estuaries Day – Saturday – approaches, evidence of the value of preserving and re-creating these aesthetically pleasing chunks of coastal habitat is increasing.

Supporter Spotlight

Although it’s long been known that marshes and wetlands are key to the growth and survival of many marine species, a new study released earlier this month by Duke University and Oregon State University shines light on a lesser-known fact: destroying them releases copious amounts of carbon into the atmosphere.

According to a Duke News press release, “The analysis in the study provides the most comprehensive estimate of global carbon emissions from the loss of these coastal habitats to date – 0.15 to 1.2 billion tons – and suggests there is a high value associated with keeping these coastal-marine ecosystems intact, as the release of their stored carbon costs roughly $6-$42 billion annually.”

“On the high end of our estimates, emissions are almost as much as the carbon dioxide emissions produced by the world’s fifth-largest emitter, Japan,” said Dr. Brian Murray, director for economic analysis at Duke’s Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions in Durham. “This means we have previously ignored a source of greenhouse gas emissions that could rival the emissions of many developed nations.”

The press release states that this carbon, captured through biological processes and stored in the sediment below mangroves, sea grasses and salt marshes, is called “blue carbon.” When these wetlands are drained and destroyed, the sediment layers below begin to oxidize. Once this soil, which can be many feet deep, is exposed to air or ocean water, it releases carbon dioxide over days or years.

The study examined the amount of carbon sequestered from the atmosphere by the slow accretion, over hundreds to thousands of years, of soils beneath these habitats. Previous studies had focused only on the amount of carbon stored in these systems and not what happens when these systems are degraded or destroyed and the stored carbon is released.

Supporter Spotlight

Linwood Pendleton |

Todd Miller |

“These coastal ecosystems are a tiny ribbon of land, only six percent of the land area covered by tropical forest, but the emissions from their destruction are nearly one-fifth of those attributed to deforestation worldwide,” said Dr. Linwood Pendleton, the study’s co-lead author and director of the Ocean and Coastal Policy Program at the Nicholas Institute.

“One hectare, or roughly two acres of coastal marsh, can contain the same amount of carbon as 488 cars produce in a year. Comparatively, destroying a hectare of mangroves could produce as much greenhouse gas emissions as cutting down three to five hectares of tropical forest.”

Todd Miller, director of the N.C. Coastal Federation, an environmental group long involved in efforts to preserve and enhance wetlands, hailed the study. “It adds to the level of information … about the value of these habitats,” he said.

What’s especially striking, Miller said, is that while the total amount of coastal mangrove and salt marsh is relatively small compared to the amount of rain forest in the world, the coastal habitat appears to play a much larger proportionate role in harboring the carbon that otherwise would be released to eventually contribute to global climate change.

In fact, he said, it’s believed that salt marshes worldwide are responsible “for taking up and sequestering about half the carbon” emitted each year by global transportation sources.

The critical role of these ecosystems for carbon sequestration has been overlooked, the Duke study said. “These coastal habitats could be protected and climate change combated if a system—much like what is being done to protect trees through Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD)—were implemented,” the press released stated. “Such a policy would assign credits to carbon stored in these habitats and provide economic incentive if they are left intact.”

“Blue carbon ecosystems provide a plethora of benefits to humans: they support fisheries, buffer coasts from floods and storms, and filter coastal waters from pollutants,” said Emily Pidgeon, senior director of Strategic Marine Initiatives at Conservation International and co-chair of the Blue Carbon Initiative, added in the Duke press release.

“Economic incentives to reverse these losses may help preserve these benefits and serve as a viable part of global efforts to reduce greenhouse gases and address climate change.”

Miller said that while the U.S. has not officially embraced “carbon credits,” it has been occurring, and some landowners in North Carolina and elsewhere in the country have participated in such programs, and utilities in Europe and here are “looking our way.”

If economic incentives for preservation of “carbon sinks’ take off, he added, that could enhance the ability to fight climate change.

Meanwhile, the federation also is engaged in potentially groundbreaking work to determine the impact that restoring coastal salt marshes could have on mitigating global climate change.

USGS scientists install devices to measure carbon uptake at North River Farms in Carteret County. |

The U.S. Geological Survey early this year installed 35 measuring devices on the organization’s property at North River Farms in eastern Carteret County.

Through grants from the N.C. Clean Water Management Trust Fund and others, the federation and private partners have bought or obtained control of almost all of the 6,000-acre farm, and have since then been working to restore marsh and forest habitat that had been either severely compromised or destroyed by years of farming activity. So far more than 2,300 acres have been restored, and the goal is to restore a total of up to 5,100 acres within the next decade.

Volunteers and federation staffers have plugged old drainage ditches and spent countless hours putting in untold numbers of native marsh plants and trees in what is by far the largest project of its type in the state and one of the largest in the nation.

The idea has been to improve water quality in nearby shellfishing waters – vegetation filters out pollution and sediments before they reach the water – but Miller said the work also presented a perfect opportunity to glean some answers to a question about which there is little worldwide information: Just how much of a role can marsh habitat restoration play in lessening the impacts of climate change?

He said the research and partnership – which also includes N.C. State University and Duke – is measuring greenhouse gases released from the soils at the restored North River Farms site and will relate these measurements to salinity, vegetation type and to the global carbon budget.

The wetland restoration site at North River Farms provides an ideal location for measuring the gases in different types of restored habitats, he added, because in addition to salt marsh, it also includes restored bottomland hardwood forest.

It’s also near natural marshes and forests that can be used for comparing the differences between gas emissions from restored and natural areas. The USGS installed the measuring devices in the natural habitats, too.

Gas samples are collected every 45 minutes and analyzed for carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases.

The first phase of the project, which began early in 2012, involves measuring the emissions, and is expected to last about one year. Although USGS has not yet released any data, some should begin coming early next year. Miller said that if the early results are promising, there should be more work long-term. And if it turns out that restored marsh can play a major role in sequestering carbon, Miller said, the study should, like the Duke and Oregon study, serve to emphasize the need for more restoration and encourage preservation of existing marsh, which worldwide in recent years has been disappearing at what many consider and alarming rate.

The Duke-Oregon work was funded by the Linden Trust for Conservation and Roger and Victoria Sant. The paper, “Estimating Global ‘Blue Carbon Emissions from Conversion and Degradation of Vegetated Coastal Ecosystems,” is available online.

Friday: Oyster reef as carbon sinks