Reprinted from Susan’s Blogue

WILMINGTON — Most days, there’s barely a ripple in the placid ponds that dot southeastern North Carolina. Many of them sit in relative isolation from Wilmington’s busy-ness. Visiting the beauty and quiet serves as balm. I’ve watched pond fishing from afar, and used to think it was a random sort of exercise reserved for the most complacent and passive among us, but over the past year, I’ve learned I was wrong. It was interviews, an excursion and fishing journals that changed my mind.

I found that serious pond fishermen are as focused on their avocation as hounds are to a hunt. What’s more, there’s a sort of cunning going on there that amazes. The language of fishing should have been a clue: bait, lure, angle, hook – but it really was a surprise to learn that many intelligent human fishermen spend lots of time trying to out-think their prehistoric prey. The good news, it seems to me, is that pond fishing is an elemental battle of nature in a world that becomes increasingly artificial; it can provide delectable entrees; and it keeps a lot of people happy, busy and out of worse trouble.

Supporter Spotlight

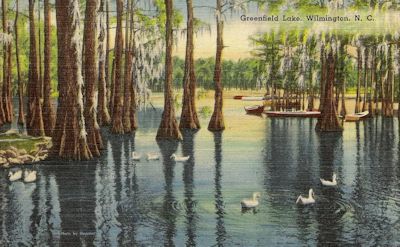

Greenfield Lake in Wilmington was a favorite destination for local pond fishermen. This postcard is circa 1910. |

The written records I studied spanned 110 years, beginning in 1901, when Luola Sprunt reported on an outing with her father, Col. Kenneth M. Murchison, and son, James Laurence Sprunt. “Went fishing at 2:30 p.m.,” she wrote, “and caught ten whopping rock fish – one about 15 inches or more by JLS, and another nearly as large by Col. KMM. Tried moonlight fishing but it was a fluke.”

Luola, a genuine Southern Belle, continued to fish from time to time, and so did her daughter-in-law – Annie Gray Sprunt, another Belle who didn’t shrink from the unattractive aspects of snaring creatures ichthys.

In 1907, Wilmingtonian Theodore Gwathmey Empie, grandson of Dr. Adam Empie began writing a journal that included hunting and fishing trips. Empie was a legendary fisherman who won many tournaments and trophies through the years. He was president of Carolina Metals Products and lived at 209 South Fifth St. in Wilmington.

Though much of Empie’s fishing took places in the ocean or rivers in North Carolina and Canada, his favorite ponds and lakes also are featured in the journal. The waters covered a lot of ground: Greenfield Lake, McIlhenny’s Farm, Smoky Lake, White Lake, Alligator Creek, Moore Lake, Island Lake, McKoy’s Pond, Rat Island, Mill Pond, Ness Creek (Wrightsboro), Kidd’s Landing at Squaw Lake and Lake Waccamaw.

Empie’s fishing buddies included George T. Clark, Martin Williard, Sr., Eugene Berry, Robert R. Bridgers, J. L. Campbell, B. H. Bridgers, Rob Calder, Milton Calder, Dr. R. W. Hogue, George Kidder, Theodore Lovering, Sid Williams, and Theodore’s brother, Brooke Gwathmey Empie. The bait they used ranged from that that was too usual to mention, to drum throat, liver, “formaldehyded shrimp”, and blue fish.

Supporter Spotlight

Merely traveling to a fishing venue in those days was seldom without frustrations. “Horseless carriages” still had plenty of kinks, and roads throughout southeastern North Carolina were famous statewide for being rough ones. The following account, presented unedited, describes a single fishing trip to Rich’s Inlet, but serves as a good example of automotive frustration during that era.

Theodore Empie writes:

The Theodore Empie home in Wilmington. Photo: Susan T. Block |

“October 9, 1910. Junction Restaurant at 4 am. Bridgers and Calder came in at 5 am looking like a comedy team stating they were late because they wanted to be late and had trouble with the auto. After breakfast got as far as Front and Market and found machine out of gear. Fixed machine after one hour of work and hunted down the sewer for bolt that Bridgers let fall.

“Went (within) a mile of the Nixon House, found the gasoline escaping because of bushes opening the exhaust pipe and saw that one tire had gone off the rear wheel. Drove down to sound, sand flies biting lively. Decided to fix wheel when we got back.

“Went to fish and fished under ideal conditions and caught nothing but one drum weighing about 1 1/2 lbs, which Bob Calder secured, and also one Blue Fish. Saw fish striking in channel and B. Calder and myself went after them. He caught two blue fish and threw away a squid. I caught four blue fish and a trout, and both of us were nearly eaten alive with sand flies. Coming on back they nearly devoured us, and when we arrived at the auto they were biting furiously. Bridgers at this point (late afternoon) threw away the lunch saying we would be in town for supper.

“We decided to run to the main road and fix the tire. After we had gone about a mile, examination showed one of the steel rims which held the rubber tire had been lost in this mile. We looked for it in the dark, and not finding it enlisted a negro who did find it. It had been sprung , so it required 1 1/2 hours to put it on the tire.

“We then came home uneventfully; stopped at my house for a drink of whiskey as Milton Calder had the key to all the Calder whiskey, and Mr. Bridgers left me saying, ‘Theo, you must admit there is no place like Rich Inlet to fish for Drum.’ ”

Empie supplemented his fishing and hunting experiences with ornithological observations, and became Wilmington’s leading expert. He learned to mimic the various birdcalls too, and gave bird speeches and demonstrations to clubs and school groups for many years.

In 1942, fearing much that he had learned would be lost at his death, he named Mrs. Cecil (Edna) Appleberry to succeed him as local bird expert. She continued and grew the Empie bird tradition, founding the Wilmington Bird Club, and becoming a nationally recognized champion for the appreciation of birds, and conservation of their optimum environments.

Today, Theodore Empie (1872-1947) is known best as the donor, with wife, Evelyn, of the land that became Empie Park.