Last of three parts

Reprinted from the Island Free Press

RODANTHE — Images from those first few hours in Rodanthe, Waves and Salvo on Hatteras Island will stay with me forever. It was much different than Hatteras village after Hurricane Isabel in 2003 where buildings and belongings were simply eradicated — gone.

Supporter Spotlight

The three villages were still standing but brutalized in a more subtle manner that wasn’t always easily noticeable. Water from Pamlico Sound kept coming all Saturday night as residents climbed onto furniture, into attics or were rescued by personal watercraft in the black of night as houses filled with tide that was head-high by some reports. When the waters receded, most of the houses still stood, but many were ruined forever.

Our first drive to the small inlet at Mirlo Beach was intense. There was a boat sitting on top of a fence, perfectly balanced. Tombstones were knocked to the ground. Retail stores had their fronts and backs blown out and their merchandise strewn everywhere.

Elsewhere on the CoastHurricane Irene sat over North Carolina for 12 to 14 hours after making landfall near Cape Lookout on Aug. 27, 2011. It triggered a storm surge that exceeded previous hurricanes and surprised many. Irene was, after all, “only” a Category 1 storm. But give a Cat. 1 it’s due. Irene’s storm surge was 9.3 feet in Aurora, for example, up to 9 feet at Pamlico Beach and 8.2 feet in Belhaven. All are in Beaufort County. More than a third of North Carolina’s 100 counties suffered damage, with federal emergency declarations for individual and/or public assistance issued in 38 counties. Away from the beaches, Beaufort, Pamlico and Hyde counties suffered the worst damage, state officials say. Supporter SpotlightStatewide, the storm caused more than $1.2 billion in damage and killed seven people. At the storm’s peak, 660,000 people were without power. |

It was hot during this stretch of time, typical post-hurricane weather. The humidity levels were wicked and the mosquitoes unrelenting. For storm victims, there was no relief from either because there was no electricity and sometimes no home.

The most awful sight I remember was the people sitting on their front steps not knowing what to do. It was the second morning since the storm, and no one had yet come to help them. House after house, they just sat and stared, lost. It reminded me of some of the post-Katrina scenes. Donny (Anne’s husband, Don Bowers) wouldn’t take any photos; these were people whom he knew and had gone to school with. These people were proud but vulnerable.

We went as far north as the road would take us. The broken highway was barricaded and guarded, and the southbound lane sunk or missing. But just ahead, it all ended abruptly, stopped by an inlet that flowed from ocean to sound. Both of us sat in the back of the truck amazed at the amount of the destruction. The power poles were leaning badly and all the houses in this area had sustained massive damage. It was a mess, and it would take a tremendous amount of manpower and time to repair.

The National Guard escorted Donny past the barricade so he could photograph the area in the pink glow of sunrise. I spent this time talking with the manager of Kitty Hawk Kites in Rodanthe who rode out the storm in his apartment that was just down the street.

He had lots of stories to tell, and even though I wrote them all down, I never had time to publish them. His name was A. J. Jackson. We had never met before but our paths crossed several times over the next couple of weeks. However, our friendship would not last because he died a short time later kite surfing in the ocean.

Around the corner from the breach at Mirlo Beach, were the smoldering remains of the house built to look like a lighthouse. It was owned by Roger and Cecelia Meekins, the original owners of the famous Serendipity House that was used in the movie “Nights in Rodanthe.” They called it the Sentinel on the Pamlico.

This was another story that I never wrote. On the second night of the hurricane, the rising flood waters caused their generator to catch fire and quickly burned the house down around 9 p.m. The couple barely got out of the house in time. Roger escaped carrying his brief case and medicines, but neither wore shoes, only the clothes on their backs.

The water was over their heads. A neighbor and his wife, who was recovering from recent hip surgery, met them with life preservers and, together with their dogs, swam and bounced off the ground to a house on the other side of the street. The owner of that house and his son waved a lit lantern from the top deck to guide the two couples to safety. No one was hurt but there was nothing left of the beautiful house the Meekins had so lovingly designed and built.

Donny and I then drove over to the ocean side to check on Serendipity, which had been moved in 2009 from Mirlo Beach to save it from the encroaching Atlantic Ocean. There it stood, all strong and proud with those bright blue shutters. Over the railing appeared the smiling faces of Ben and Debbie Huss, owners of the house. They, too, had ridden out the vicious Hurricane Irene on Hatteras Island.

“She shook, she rattled, and she moved a lot,” Ben said about the house during the hurricane, “but she hung in there and we have very little damage.”

They did lose the six gallons of ice cream in the freezer.

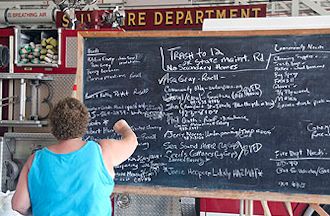

The Salvo Volunteer Fire Department was a hub of activity after the storm. |

Meals were served to residents and workers at the Rodanthe-Waves-Salvo Community Building. Photos:Don Bowers, Island Free Press |

We moved around the island all morning talking to people and hearing their stories. Because our house phone worked, we collected phone numbers and messages from dozens of people asking us to contact their family and friends off-island to let them know they were safe. Apparently, we had one of the few working phones on the island that could call long distance.

Donny had arranged to take a flight to get his first aerial photographs of the inlets that day so our first trip was cut short by this opportunity. Coming back into Buxton that afternoon we saw lines of trucks and cars in both directions at two open gas stations. It was day three without electricity and residents needed gasoline to run their generators. It was a crazy scene and reminded me of the gas crunch in the ‘70s.

Donny barely made the flight with local pilot Dwight Burrus of Hatteras, and I used this time to catch up with Irene Nolan at her office – which, at the time, was her air-conditioned vehicle. There was so much going on and communications were hampered, yet the news had to get out. It was all so rudimentary but we managed. She edited my work on my laptop and I would run to the electric company to e-mail articles and photos to Donna, who continued to work from Raleigh.

Many readers may not remember this but it was 11 days before those who evacuated could return home. We were on lockdown until fundamental services, such as food, water, electricity and fuel could be established and maintained. The Coast Guard patrolled the waterways and marinas and the airport was watched by law enforcement to keep folks from flying in. Who was allowed to use the emergency ferries was tightly controlled. A curfew was also in affect from 9 p.m. until dawn, which made my late-night trips to use the electric company’s Wi-Fi rather nerve wracking. However, we never got stopped.

For nearly three weeks, Donny and I made daily trips up to the Rodanthe, Waves and Salvo. The amount of issues to be covered was endless. The Community Building, along with the local fire departments, became the central locations for everything. This is where people ate, where donations were dropped, where medical attention began, where housing problems were addressed, where meetings and church services were held and more. Most residents lost their cars in the flood and getting around was challenging, so these localized centers were incredibly helpful.

The temporary ferry dock that ran from Rodanthe to Stumpy Point, which was also devastated by Hurricane Irene, had its own set of problems. It was our vital connection to the mainland. Every piece of heavy equipment that was used to fix the road came by this ferry. All fuel came on this ferry. The steamy black asphalt had to travel to us by this ferry. Yet, the storm had caused shoaling in many areas of the channel, and ferry boats could run only at high tide most days. The channel leading into the Rodanthe dock was so narrow that only one ferry could be in it at a time, and the dock was only big enough for one ferry. Many times, the ferry would have to wait out in the sound until the channel was clear of boat traffic, which would take an hour or two.

Gov. Beverly Perdue, right, talks to volunteers in Waves after the storm. |

The debris piles grew mountainous in size. Photos: Don Bowers, Island Free Press |

Several ferry workers pulled long shifts without any days off only to get off work and spend the night on a neighbor’s couch because their own home was made uninhabitable by Hurricane Irene.

By Wednesday, Aug. 31, signs of recovery were beginning to show. Volunteers from the lower villages had mobilized and were helping the people of Avon, Waves, Rodanthe and Salvo clean up and protect their homes from mold. This was a horrible job – pulling out wet carpet and soaked insulation from underpinning, pulling out drywall, spraying Clorox, or just picking up huge amounts of debris which could be anything from trees to the neighbor’s dock.

All trash was required to be brought to the sides of N.C. 12 where it would be collected. By the last day of August, the piles were huge and growing. It looked awful and sad. Furniture, pianos, clothing, papers – it was all piled along the road.

Large dump trucks that pulled a huge trailer were brought in and funded by FEMA. The Salvo Day Use Area, located on the sound side just south of Salvo, became the temporary dumping ground. It was organized into metal, wood or other materials, and it grew into a monstrosity.

Entire houses were torn down and taken to the edge of the road. These super-sized dump trucks were equipped with yellow cranes that would scoop up everything and take it to the dumping area. By the next day, there would be more trash and debris along the road, which looked like it had never been touched.

People were often overcome with emotion when they saw the size of the temporary dumpsite. It continued to grow until N.C. 12 reopened on Oct. 10.

Also by the end of August, Donny and I had tested the power of the inlet at Mirlo Beach. We devised a plan to ride our bikes up to the big inlet on Pea Island which was about five miles north of Mirlo. We checked the tide charts and picked a time before low tide to carry our bikes across at Mirlo and ride north to take the first photos of the inlet on the ground on the south side.

In the early afternoon hours of Sept. 1, Donny and I discreetly took the bikes out of the back of the truck and made our way to the shallow part of the inlet, carrying the bikes high as we waded across. The road on the other side was like ribbon candy with dips and valleys that were chest high. On the dunes, we could see the high-water mark left by the sound water from the week before. To our surprise, it was over our heads all the way to the inlet.

It took some time to negotiate the broken surface, but we finally got to some smooth road and battled the 25-30 mph headwinds all the way to the Pea Island Inlet. Once there, we walked towards the ocean and through the fingers of the newly cut inlet. This wasn’t an easy walk.

The inlet was a sight to behold. There were multiple cuts with one major one that ran from sound to ocean. The fast moving water was clear and blue. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife buildings were severely damaged, with one of them draped on the edge and falling into the water. In time, all three buildings would be swallowed by the sea.

The electric linemen were working on the poles in an effort to straighten and repair. On the other side of the inlet, there seemed like there were lots of parked vehicles and dozens of people scurrying around. There were so many kinds of repair issues around this area — transportation, electricity, phone, and cable just to name the obvious. Recovery plans were still in the making at this point. We didn’t know yet how the road would be repaired, but it wasn’t going to be quick.

Hurricane Irene cut a new inlet at Mirlo Beach on Hatteras Island. |

With the wind at our backs, the ride back to Mirlo Beach was much easier. This would be our only bike ride to the inlet. When the Mirlo Inlet became somewhat negotiable by truck, we started getting regular rides with the N.C. Department of Transportation road crews. We met some great guys that gave it their all to get that road repaired as quickly as humanly possible. Oh, did I mention that I accidentally dropped the bike in the inlet when crossing back? Oops.

Many readers may know that I have a real soft spot in my heart for animals. Driving home from Rodanthe one day, we saw a pelican, acting sickly and standing by the road. We caught it without much trouble. Donny tied a rubber band around the tip of its beak to keep it from biting, wrapped it in a towel to keep it still, and took it to Frisco where local wildlife rehabilitator, Lou Browning, could attend to him.

The bird was exhausted from the storm and unable to hunt. After much needed food and rest, it was released back into the wild. Lou’s rehab center had dozens of birds suffering as a result of the hurricane, mainly the ocean bird known as the shearwater. Many of these waterfowl were too far gone for Lou to save.

The morning following our bike ride to the inlet, I got a call that the house known as Tail Winds had collapsed. Tail Winds had become the first oceanfront house people saw after Serendipity was relocated. It was painted a beautiful shade of blue with lots of white trim. The windows had been boarded up for protection during the storm.

The house simply fell in on itself, according to witnesses. A surveyor heard a loud crack that caught his attention. He watched the house fall to the ground. We were surprised that this house collapsed because outwardly, it didn’t appear to be in peril, unlike several other houses that surrounded it.

The house and everything in it was smashed to pieces by the ocean that was churned up by Hurricane Katia, which passed offshore. The broken-up house and all of its contents covered the beach or washed into the inlet. A lot of this debris is buried under N.C. 12 today.

Our attention was quickly turned to Tail Winds neighbor, the Black Pearl. This oceanfront home was seriously listing. For days, we watched and photographed it as it continued to lean towards the ocean. But, the Black Pearl still had some life left in it and it held on. The owners were able to secure a permit to move the house back on that lot and save it. They are hopeful that it will be able to be rented by Labor Day weekend.

There were plenty of meetings to attend.

Warren Judge |

County Commission Chairman Warren Judge traveled from Manteo to Hatteras Island often. He always parked his vehicle at Stumpy Point and walked onto the ferry, saving the valuable ferry space for someone who needed it. There was always someone to meet him and take him around. And the person was generally Allen Burrus, the commission’s vice chairman from Hatteras village. They were always around, meeting with the public and working hard for a quick recovery. One needs to keep in mind that Hatteras Island was only one of the areas in Dare County devastated by Hurricane Irene.

On Sept. 30, Gov. Beverly Perdue flew in to see the damage in the northern villages and talk with a few storm victims. Donny and I were lucky enough to ride around with her entourage and to have the opportunity to speak with her directly. She pledged her total support to put the island back to the way it was in spite of some of the opinions being talked about in the mainstream media that they shouldn’t build “the bridge to nowhere.” She was warm and approachable to the victims who wanted to speak with her.

The triumph of the human spirit is what powers people to do amazing things such as fixing what the storm ruined, and this needs to be the take-away from every article written about Hurricane Irene. Through it all, the island continues to recovers today. We still drive over a temporary bridge, and there are some people who still are waiting for their homes to be finished.

The seven weeks of isolation following the attack of Hurricane Irene was surreal and weird. We ate differently, our routines were disrupted, and clocks ran fast on generator power, gaining about a half hour per day. Light bulbs glowed and faded. Electronics worked most of the time but not always. It was January when the final repairs were completed on the electric lines that power the island.

In the end, my truck battery died prematurely probably from all those late nights working in front of the electric company with my laptop plugged into the cigarette lighter and air conditioning running on high. The bicycle that I dropped in the inlet at Mirlo Beach rusted pretty quickly from the salt water in spite of Donny’s efforts to clean it.

Unfortunately, the laptop didn’t make it. It held on until the bridge opened and with the job complete, it gave up and just wouldn’t turn on anymore. It had done its job well.