First of two parts

I grew up “on the sound,” Masonboro Sound, one foot on land and one in a boat – literally. My parents built a home near the entrance to Hewlett’s Creek about 1950 and gave me freedom to roam land and water, provided I ate some meals with them, slept at home (mostly) and attended school. I was blessed with friends who had the same privileges and shared my interests in the outdoor world. Before I tell you about our idyllic life, let me introduce you to New Hanover County as I knew it in 1950, now utterly transformed.

The population of the county (63,272) was largely within Wilmington (45,043), mostly living in the space presently bounded by the Cape Fear River, Shipyard Boulevard, Kerr Avenue and Smith Creek. Wrightsville Beach, which was all on the beach island per se, was much as it looks today, with almost no winter residents, while Carolina Beach was considerably smaller than today.

Supporter Spotlight

The rest of the county was largely pine savanna, with only scattered homes along the sounds and the creeks entering them. There were few “No Trespassing” signs anywhere – none on the beaches other than Wrightsville and Carolina, all the way up to Topsail Island, because there was literally nothing man-made on them. There was a lighthouse on Bald Head but no development or access except by boat.

Taken from the point where the Vaughans lived on Hewlett’s Creek, the photo looks up the creek at low tide. The white house in the background belonged to Addison Hewlett Jr., a descendant of the family for which the creek was named. Photo courtesy of Mike Vaughan. |

That was it!

In fact, my friends and I felt all the other beaches were ours and always would be. In particular, we used to enjoy camping out on Figure Eight Island and Little Topsail Island and fishing in Mason’s Inlet, Rich’s Inlet and Elmore’s Inlet (aka Old Topsail Inlet). For boys, we had good taste.

Supporter Spotlight

Summer and winter, all months, I lived a vital part of each day on Hewlett’s Creek and the surrounding marshes, waters and islands, especially Masonboro Island, almost visible from our home.

Two friends, Sandy and Rob McEachern, who lived on the opposite side of Hewlett’s Creek, hunted, fished and shrimped with me. Their father made us a 100-foot-long seine we used for shrimping on out-going tides in the creek on summer mornings. We would lazily swim and drift down creek with the net, stopping occasionally to pull it to shore and empty it of assorted fish, crabs and shrimp. The net contents sometimes included bizarre and beautiful creatures, too, such as Aplysia (giant sea slugs), colorful starfish and a variety of edible and non-edible crabs. Black skimmers were always with us, as well as lots of oyster catchers, willets, herons of all types, egrets and shore birds.

By noon we headed home with several bushels of shrimp, and then, to avoid the work of heading the shrimp, called ladies in Wilmington whom we knew were happy to get very fresh shrimp at a good price and had maids to handle the heading job. Budding entrepreneurs.

The birds on and around Hewlett’s Creek were varied and endlessly fascinating, and I constantly expanded my life list. At higher tides we frequently had ospreys and bald eagles fishing for mullet in the creek, and it was quite usual to watch eagles stealing the ospreys’ fish right in front of our house.

Ducks were common on the creek, too, and in winter we boys hunted for them. The first I proudly brought home were two red-breasted mergansers. I explained to my mother how to prepare them, using only the skinned breast meat, but the results still tasted more like fish than fowl. No more ducks were cooked in our home, though I tried valiantly for the teal, black ducks, ruddy ducks, bufflehead, scaup, pintails and occasional brant that flew past our blind.

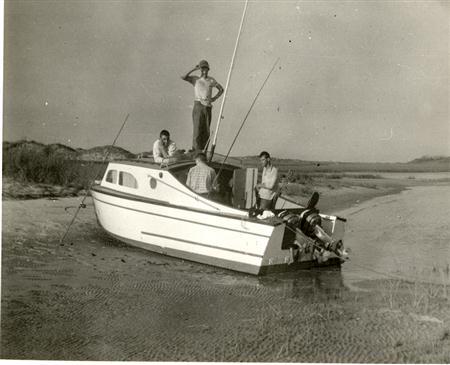

Harry Latimer, Mike Vaughan’s friend and now brother-in-law, stands on the cabin roof of his family’s boat, the Mary A., in which Vaughan and his friends spent many happy hours. Vaughan thinks the photo was taken behind Figure Eight Island, but it may have been Little Topsail. Jim Evans, sprawled out on the cabin roof, still lives in New Hanover County. Vaughan recalls a day when the boys were anchored in an inlet fishing, with Jim up there on the cabin roof, when he suddenly hooked a large channel bass. He couldn’t fight the fish and hold onto the roof, too, so the boys had to take turns up there, holding onto him by his belt. Photo courtesy of Mike Vaughan. |

One special place where we hunted ducks was Big Bay inside the marshes behind Masonboro Island, reached by going up Houseboat Creek, which entered Masonboro Channel right behind Masonboro Inlet. The Bay was (is?) quite large, many acres in area at high tide, and the McEachern boys’ father told us that until the Great 1933 hurricane it was full of eel grass which attracted flocks of canvasback and other ducks in winter. In summer we would often spend the day on the island, collecting buckets of clams at low tide in the creek’s clean, sandy pools.

I also hunted and fished with two other friends, Harry Latimer and Jim Evans. The Latimers had a 23-foot cabin cruiser in which we spent many, many hours fishing for channel bass and bluefish in the inlets north of Wrightsville Beach. The procedure was to anchor in the inlet as high tide began to recede and to trail our lines out in the current, with chunks of mullet on stout hooks. Hours of sitting and talking about the things that eternally interest teenage boys, while waiting for fish, were punctuated by minutes of frantic action when they arrived, sometimes on a grand scale. I vividly recall an afternoon when Masons Inlet literally turned red with a big school of large channel bass. The whole inlet, as far as we could see. We took turns standing on the top of the cruiser cabin to watch in awe.

In retrospect, I realize now that it was highly significant that, by and large, we were often the sole people on the beach or creek or ocean in these adventures. Thus our sense of unique ownership of what lay around us.

Likewise, for better or for worse, our enjoyment of all these seaside activities was increased by the fact that, apart from encountering few, if any, No Trespassing signs, there were also virtually no regulations affecting us, apart from the need to obtain hunting licenses. Saltwater fishing of all types was completely un-regulated, with a few exceptions pertaining to commercial fishermen. For practical purposes we lived in a state of nature, enjoying nature, by the sea.

Wednesday: Egg bread and Christmas bird counts

This article originally appeared in The Skimmer, the newsletter of the Cape Fear Audubon Society.