COLINGTON — Just as the sun is peeking over the marshes and pine hammocks, Murray Bridges’ small Privateer is inching through murky backwaters towards the open waters of Roanoke Sound, where rows of hot pink buoys mark his crab pots that rest solidly on the bottom.

Bridges makes this early trip out to his pots early six mornings every week. It’s taxing at times but Bridges and mate Lannie “Dolan” Belangia, Jr. see no other substitute for the beauty that comes with working on the water at dawn.

Supporter Spotlight

A native of Wanchese, Bridges has spent most of his life on the water. Whether it was fishing off the beach from a dory or stringing gillnets in the sounds, Bridges has spent his life immersed in the natural environment.

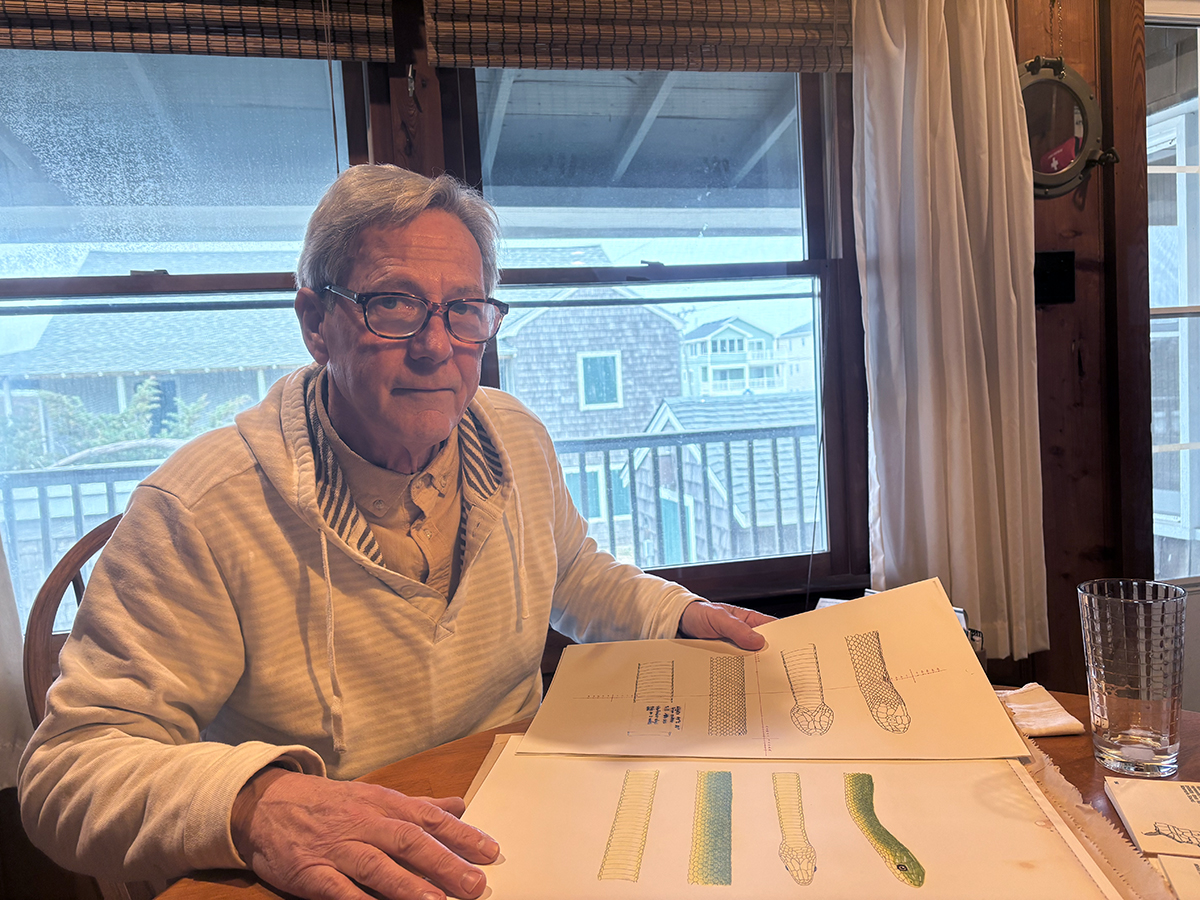

Murray Bridges |

After 22 years as a merchant mariner, the experienced waterman returned to his natal waters and opened Endurance Seafood in Colington in the 1970s. It was here that he became a pioneer for the softshell crab industry in Dare County. His backyard business became a success by marketing North Carolina softshell crabs through expanded markets in the northern states.

“We ship our crabs all over, from Washington DC to Maryland. These crabs we catch today will probably see the hard crab markets in New York,” Bridges explained.

Today, Bridges’ business exists as a quintessential piece of the hard crab markets locally and along the East Coast.

Bridges, a spry 78, stands sturdily behind his homemade starboard console during the run towards the Roanoke Sound. While the glare of the angled morning sun reflected harshly upon the boat’s deck, Bridges still refuses to wear sunglasses.

Supporter Spotlight

“They’re bad for your eyes,” chuckled Bridges, pointing at Belangia’s sunglasses, “I’ve never worn them, and I can still see just fine.”

On this particularly brisk morning, our arrival to the first string of pots nestled east of Wanchese generates swift action by Bridges and Belangia. While Bridges wields a long hook to snatch the buoys, Belangia prepares the stern of the boat for his well-practiced culling routine. Once the crab pot line is inserted into the pot puller, Bridges awaits the wire pot’s arrival to the boat where it will be opened, emptied, re-baited with menhaden and tossed back into the water to await collection the following day.

Despite the commotion of snapping claws, Belangia effortlessly culls between females, males, pre-molt and soft crabs – all before the next pot is placed on the cover boards.

“I guess you could say I’ve looked at a lot of hard crabs,” he said grinning. “I’m about the sixth generation of a commercial fishing family. It’s pretty much second nature by now.”

Beautiful Swimmers

Scientifically referred to as Callinectes sapidus, or “beautiful swimmer,” the blue crab has proven to be a profitable gem for North Carolina’s seafood industry. According to the N.C. Department of Marine Fisheries, blue crabs are the top commercially harvested species in the state. In 2011, over 30 million pounds of blue crab were harvested – a number worth over $21 million to North Carolina.

|

Predominantly collected between May and October, the blue crab is most recognizable to consumers fried as a soft shell or steamed to a bright orange in a hard shell. According to North Carolina Sea Grant, nearly all of commercial fishermen in the state use wire crab pots. They scatter coastal waters with more than 800,000 each year.

Pre-molt, or “peeler,” crabs are those that show signs of molting and can be characterized by color differences in the crab’s shell and backfin, or apron. These subtle characteristics indicate the stage of a crab’s molting cycle. When the coloration is just right, Bridges and Belangia collect the crab for its transition into a soft shell. They’re held in tanks at Endurance until molting occurs. Once the crabs are soft, they are packed and shipped to their destination.

According to a 2002 study by Dr. David Eggelston of N.C. State University, soft shell crab harvest has truly expanded the potential of the blue crab market. The shelf life of a hard crab is typically quite short, which limits their ability to be shipped long distances. However, the soft shell crab can be frozen and will keep its fresh flavor for several months.

Traditional Industries on the Brink

Over the years, commercial fishermen have faces numerous obstacles – higher fuel process, cheaper imports, more rules and regulations. Add to that the steady disappearance of local fish houses. As the places where fishermen go to weigh and sell their catch, fish houses are important to the survival of the commercial industry. But they are in trouble. According to a 2007 study by N.C. Sea Grant, higher operating costs, covetous waterfront property and decreasing water quality led to a near 35 percent decline in the state’s fish houses from 2000 to 2006. And the declines continue.

Even throughout the numerous famines of the commercial fishing industry, Bridges has managed to maintain Endurance Seafood. He sells his soft crabs Northern states to local restaurants and residents. AS a result, soft crabs from Colington are a known brand.

Dolan Belangia work for Murray Bridges and learns from him. |

“When we get our soft shells in, everyone around here knows. All it takes is a phone call,” laughed Bridges.

While political and economic factors greatly affect the health of commercial fisheries, habitat quality is just as important an issue.

Upon returning to the dock with the early-afternoon sun well over the trees of the protected creek, Bridges meandered through the maze of soft shell shedders to look for recently shed crabs. While his seasoned hands collected soft shells, Bridges explained frustration over the current state of water quality and fisheries regulations. As far as Bridges sees it, the decline in the quality of his natal waters over the years has been serious.

“The worst part is we are the ones that are out there every day. When we actually tell people what we see, it’s like in one ear and out the other,” said Bridges with a shake of his head. “It really hurts.”

Sharing the sentiment of many coastal watermen in North Carolina, Bridges sees the decline in fish populations and quality of habitat.

“There are less numbers of fish and crabs – maybe they’ve moved on, but they’re not here anymore,” said Bridges. “We can see it in everything we do. Just look at our pots – the moss buildup on the line that used to take two weeks to produce now takes two days. The water is just dirtier.”

According to a study by the N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources, 87 percent of commercial fishermen in northeastern North Carolina have less than 20 years’ experience on the water. Most fishermen, the study notes, have been actively engaged for an average of 13 years. That makes Bridges, with a lifetime on the water, an outlier.

The majority of commercial fishermen think the ability to make money in the industry is declining, but Bridges is passing along something far more valuable than money—his 70 years of experience on the water. In Belangia, 24, Bridges has a willing and eager student.

“I’ll do this as long as I can,” said Belangia, slinging another handful of she-crabs into a bushel basket teetering behind him. “I’ve never been the type meant for an office.”