Second of two parts

DANVILLE, Va. — The potential contaminants from any uranium mining in the Roanoke River basin in Virginia could have effects far downstream as the river flows on to the N.C. coast.

Supporter Spotlight

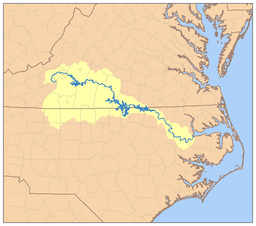

The Roanoke River, flowing more than 400 miles from Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains to North Carolina’s Outer Banks, provides water to more than one million people for drinking, farming, fishing and boating. It is the backbone of southern Virginia’s agriculture sector, valued at more than $300 million in 2007, and boasts world-class striped bass fishing, drawing thousands of anglers each year.

Roanoke River Watershed |

Described as “one of the Mid-Atlantic’s most biologically diverse rivers” by the conservation group American Rivers, the Roanoke was also named one of the country’s Most Endangered Rivers in 2011 by the same organization. Citing the proposal to mine uranium on Coles Hill near Danbury, American Rivers concluded that the river’s assets “could be irreversibly damaged by the toxic run-off” of the proposed uranium mining.

The life and legacy of this prized river is in jeopardy, said Pete Raabe of American Rivers. “This uranium operation would generate millions of tons of toxic, cancer-causing waste,” he said.

Recently, Mike Pucci, a Lake Gaston resident, created the North Carolina Coalition Against Uranium Mining. The lake is one in a chain of reservoirs along the river. The group’s goal, said Pucci, is to “wake up” the public in North Carolina to the potential impacts of uranium mining and processing far up the river.

While he notes that the debate is centered in Virginia, Pucci argues that “there’s no benefit to North Carolina, there’s only risk.” Fourteen local governments and organizations in North Carolina have passed resolution opposing lifting the ban on mining, according to the coalition web site.

Supporter Spotlight

Like many opponents, the coalition expresses concern over the potential effects a major accident failure could have for hundreds of years on natural resources and a valued water supply.

Residents from Warren County, N.C., protest at a recent uranium public meeting in Virginia. |

Virginia Beach has the same fears. Lake Gaston, which straddled the North Carolina-Virginia border, is the city’s main source for drinking water. Virginia Beach has been the most vocal local government in opposition to the state lifting its existing ban on uranium mining.

A “catastrophic failure” of a tailings disposal site would contaminate the drinking water supply coming from the lake and the river, said Thomas M. Leahy, the city’s director of Public Utilities.The city has done “worst case modeling,” he said, that establishes the likelihood of contamination with “reasonable certainty,” leading to radioactivity levels in the water anywhere from five to fifty times greater than that permitted by current federal law.

In a memo to the city manager, Leahy noted that the uranium’s location on Coles Hill was “prone to significant flooding,” arguing that the moratorium must remain in place until Virginia adopts “a permanent and sustainable culture and philosophy in which compliance with laws and regulations is only the first step to a regulatory approval.

“In my opinion, the opposite—minimum compliance with laws and regulations—is the current norm in Virginia,” he concluded.

Leahy argues that similar risks exist if mining were to occur in other river basins, such as the James, thereby threatening the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries.

URANIUM AND CHESAPEAKE BAY

Thomas Leahy |

Gov. Bob McDonnell |

The questions surrounding the impacts from mining uranium are not geographically restricted to Southside Virginia and northeast North Carolina. According to a study done by the National Academy of Sciences, there are 55 identified uranium sites in the Commonwealth. While the Coles Hill site is outside the Chesapeake Bay watershed, others are not. Many of the sites are in the Piedmont and Blue Ridge regions, where the Potomac and James and their feeder rivers flow. To date, however, only the Coles Hill deposit is “large enough, and of a high enough grade, to be potentially economically viable,” the study notes.

The current economics have not prevented debate over the impact of lifting the moratorium in these other regions. Fairfax County, one of Virginia’s most populous and politically powerful jurisdictions, is full of creeks and runs that drain into the Chesapeake’s Potomac River. This includes the historic Bull Run of the Civil War as well as the Occoquan River and Reservoir, a primary drinking water supply for the county.

Mining leases exist in the Occoquan watershed. The county’s Environmental Quality Advisory Council recently adopted a resolution recommending to the Board of Supervisors that it support the retention of the moratorium.

WHAT’S NEXT?

The debate over lifting the moratorium reached the Virginia General Assembly this year with legislators arguing both sides. Five Southside legislators penned a letter to maintain the moratorium in response to the academy study, saying that the report was “sending clear warning signals” against the mining of uranium in Virginia.

In contrast, Sen. John C. Watkins concludes that we will solve the nation’s air pollution problems only through the use of nuclear energy and favors lifting the moratorium.

Virginia can have “a full examination” on how to conduct mining to “ensure the safety of the community and of the people working in the mines,” Watkins said.

Acknowledging that the safety of the environment is an equally essential element of mining, Watkins argues that a moratorium is nothing but a not-in-my-backyard statement of “don’t bother me with the facts.”

According to the Keep the Ban coalition, more than 10,000 people have told the General Assembly to continue the moratorium and 85 government entities and nonprofit groups have expressed “deep concerns” over lifting it.

In the midst of the debate, Gov. Bob McDonnell asked the legislature to forego taking any action and issued a directive establishing a Uranium Working Group. McDonnell acknowledged in the directive that there are “important questions related to the health and safety of workers, the public and the environment” that “must be addressed before an informed determination” on lifting the moratorium should be made. The charge he gave to the working group, though, was to create “a draft statutory and conceptual regulatory framework that could be used to govern all aspects” of mining uranium in the Commonwealth. The group is to present its findings to the Coal and Energy Commission by Dec. 1, just before the 2013 General Assembly session.

Robert G. Burnley, the former director of Virginia’s Department of Environmental Quality and now partnering with the Southern Environmental Law Center in its efforts to maintain the moratorium, challenges the legitimacy of the Uranium Working Group process. He notes that the development of the “regulatory framework” is not being conducted under the open-government parameters established by Virginia’s administrative process. To further emphasize his concern, Burley notes that he has been advised that the current work products of the group are classified as “governor’s working papers,” making them inaccessible under Virginia’s Freedom of Information Act.

Confusion and criticism over the transparency of the work group’s process led Martin L. Kent, McDonnell’s chief of staff, to issue two recent letters correcting “mischaracterizations” regarding public comment, participation and openness. He advised the Coal and Energy Commission that the Uranium Working Group will “periodically report its progress and accept input from the public during four open meetings.”

“Ultimately, it is the General Assembly that must decide whether or not to lift the uranium moratorium,” notes Kent. If it does, the legislature could direct state agencies to devise regulations, using a process that “will follow the Administrative Process Act.”