First of two parts

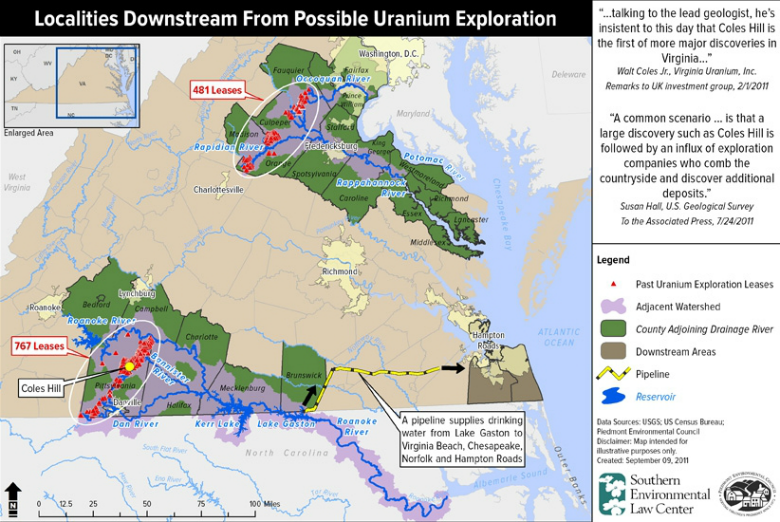

DANVILLE, Va. — There’s a debate going on up here that North Carolinians, especially those living along Roanoke River, should pay attention to. Virginia is considering lifting a moratorium to allow uranium mining. One of the world’s largest undeveloped deposits lies north of this town in the heart of the Roanoke basin, and mining it could threaten the river.

Thomas Jefferson knew little about uranium when, as governor of Virginia, he granted property in Pittsylvania County to the Coles family. Some 230 years later the gift is at the heart of a public debate that pits national energy policy and local economic opportunities against regional environmental concerns.

Supporter Spotlight

So far, the debate has:

- Raised serious doubts about the potential economic benefits for the Coles and others in Virginia with lands laden with uranium.

- Prompted a study by the prestigious National Academy of Science that confirms the risks that extraction could present across the Commonwealth and down in North Carolina.

- Driven the state’s governor to issue an unprecedented directive for the development of a “conceptual regulatory framework” for mining even while a statewide moratorium exists.

The debate has also led Rebecca Hanmer, a former senior official with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, to conclude that uranium mining presents an environmental risk to Virginia and its natural resources so great that “everything else past and present pales in comparison.”

And the river that will flow past these uranium mines continues on to coastal North Carolina.

The Uranium of Coles Hill

The Roanoke River downstream of the possible mine site. Because of the threats posed by the mine, American Rivers last year placed the Roanoke on its Most Endangered Rivers list. |

Pittsylvania County, straddling the N.C. line in “Southside” Virginia, is in the heart of the Roanoke River basin. With a history dating to 1767, this rural county hosts the city of Danville, the birthplace of Nancy and Irene Langhorne. The witty Nancy eventually married well and become Lady Astor, the first woman to sit in the British Parliament. The lovely Irene also chose well. Her husband, Charles Dana Gibson, was an artist whose satirical “Gibson Girl” illustrations defined femininity at the turn of the 20th century. His wife was one of his models.

With a median annual household income of less than $40,000 and an unemployment rate of up to 10 percent — compared to Virginia’s statewide rate of 6 percent — the county faces serious economic challenges.

Supporter Spotlight

Farming is the main occupation for many in the county, including the members of the Coles family. They currently raise cattle on land given to their ancestors by Jefferson and dominated by a hill that bears the family name. Five generations of the Coles have worked this land. For years, they grew tobacco as did other farmers in the county. Now, they want to mine its uranium.

Virginia Uranium Inc. states that it is “working to bring the economic benefits of uranium development to Virginia and advance the energy independence of America.” Its mission may be more succinctly described as wanting to mine the uranium beneath the Coles family farm and surrounding land.

Founded by the Coles, the company is Virginia-owned and Virginia-managed. It now trades on stock markets in the United States and Canada as “Virginia Energy Resources.” Its original investors included over 30 Virginia farmers and business owners, and the company says that local families still control 78 percent of the company stock. The local character of Virginia Uranium, though, is now supplemented by people with worldwide mining experience. For example, one member of its board is the CEO of Denison Mines Corp., a company that works on uranium mining around the world, from Mongolia and Zambia to the western United States.

Since 2007, $39 million dollars have been invested in Virginia Uranium’s effort to allow uranium mining in Southside Virginia, the company reports.

|

The Moratorium

Uranium was discovered on Coles Hill in 1978. Four years later, the Virginia General Assembly placed a temporary moratorium on uranium mining in the Commonwealth. The law prohibits the mining until “a program for permitting uranium mining is permitted by statute.” Virginia currently has no such program.

Uranium mining was the topic of considerable study after the ban was passed, noted John C. Watkins, a state senator. That work led the Virginia Coal and Energy Commission—a legislative commission and not an executive branch permitting agency like the Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy—to conclude that Virginia could lift the moratorium “if essential recommendations” from a uranium mining task force were enacted into law.

The legislature, though, did nothing and the moratorium stayed in effect. Virginia Uranium, which wanted to mine Coles Hill, determined at the time that mining was not economically viable.

There things stood until 2007. The company considered mining profitable again, and the legislative commission instigated two major studies. The National Academy did the first study. Its focus, according to Watkins, was whether mining could be “undertaken in a manner that safeguards the environment, natural and historic resources, agricultural lands and the health and well-being of [Virginia’s] citizens.” The second study, conducted by the Richmond firm Chmura Economics & Analytics, focused on the socioeconomic effects.

The Study Results

|

Unlike other historic locations for uranium mining, Virginia has a much wetter climate with more extreme weather events. Uranium mining in the United State has, to date, been done in dry climates. The academy study noted that “large precipitation events and earthquakes” in Virginia had the potential to “lead to the release of contaminants if facilities are not designed and constructed to withstand such an event.” The study noted that there is also a lack of technical expertise and experience in federal and state agencies for “applying laws and regulations” in climates like Virginia’s.

The academy study also raised concerns about “tailings,” the name given the waste left after the uranium is separated from the ore. Uranium tailings contain a substantial level of radioactivity that could contaminate local waters, the study said. “Tailings disposal sites represent significant potential sources of contamination for thousands of years, and the long-term risks remain poorly defined,” the report stated.

Hanmer agrees, arguing that uranium mining could leave a “legacy of toxic spoils that will not go away for centuries.”

Academy researchers advised that if Virginia were to rescind the moratorium, “there are steep hurdles to be surmounted before mining or processing could be established within a regulatory environment that is appropriately protective of the health and safety of workers, the public and the environment.”

The socioeconomic report by Chmura concluded that “the mining and milling operations would bring substantial and much-needed economic benefits to Pittsylvania County, the immediately surrounding areas and the state.”

Mining could provide 1,000 jobs annually for 35 years and an annual net economic impact of around $135 million, the report said.

Chmura specifically noted that these millions of dollars were the “net positive economic impact” after subtracting out a “broad array of potential socioeconomic costs, such as public health and the environment, and the negative ‘stigma” effects on sectors such as tourism and agriculture. However, Chmura premised its conclusions on the assumption that federal regulations would reduce these environmental and public health risks to “negligible” levels.

Should the operation and decommissioning of the mining have a “severe environmental impact,” then the net economic impact would be negative, not positive. Chmura defined a “severe environmental impact” as one where contamination of “both water and at least one other area (air, soil or noise) exceeds the limits set by current federal standards.”

Thursday: Effects on the Roanoke River

Editor’s note: A version of this story first appeared in the Chesapeake Bay Journal.