Source: N.C. Department of Transportation

Supporter Spotlight

First of two parts

EAST LAKE — As the residents of this little community see it, the last leg of the proposed U.S 64 widening project is threatening to all but wipe them off the map, and they say there’s not even a good reason for it.

The tiny working-class community on the western end of the rural Dare County mainland sits on swampy land that since 1984 has been surrounded by Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge. The two-lane strip of asphalt fronting East Lake was built decades ago, but more than a century after the pre- Civil War community was founded.

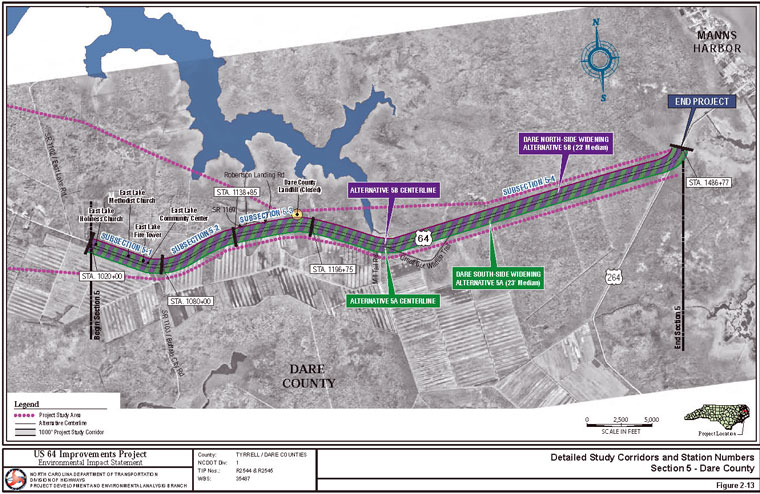

Now East Lake residents fear for their future. If the road is widened to the north, it will affect fragile wetlands and refuge land, a proposal the refuge doesn’t favor. But if it’s widened to the south, it will decimate numerous houses and historic buildings in East Lake, where families like the Cahoons, Sawyers and Twifords have lived for generations.

“They’re very upset,” said resident Rosemarie Doshier, a Dare County Realtor. “They feel like nobody cares about us.”

Supporter Spotlight

The N.C. Department of Transportation says that the road must be expanded to four lanes to prevent accidents and make hurricane evacuation faster. A draft environmental impact statement was released last month for the 27.3-mile project, the final section of 200 miles of U.S. 64 from the state capitol to the Outer Banks that’s slated for widening.

But East Lake residents question why such an expensive, disruptive project is necessary, or if traffic is a problem in the first place.

“No, never — even during hurricanes, ” Doshier said. “That traffic does not back up there. The only time is when there’s a wreck or the when the bridge is open.”

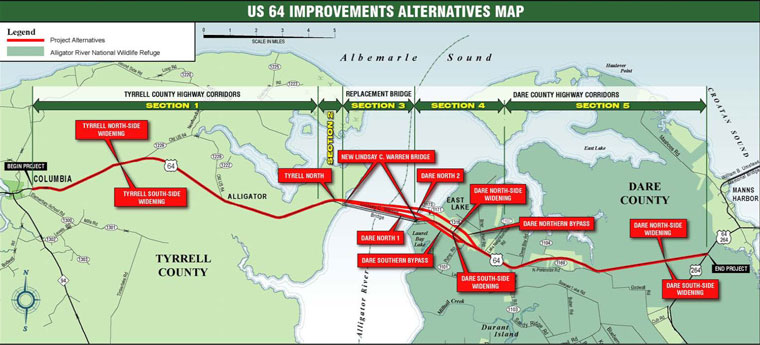

Replacement of the 52-year-old Lindsey C. Warren Bridge, a 3-mile swing-span over the Alligator River that opens for boat access, is a welcomed part of the proposed project, which is estimated to total $356 million to $400 million. Stretching between Columbia and Manns Harbor, half in Tyrrell and half in Dare counties, the proposed project would widen the road to the north or the south, or if necessary, it could zigzag either direction to avoid conflicts. Most of it will include a 46-foot median, except for a section in Dare that will be 23 feet, the minimum required.

Replacement of the 52-year-old Lindsey C. Warren Bridge, a 3-mile swing-span over the Alligator River that opens for boat access, is a welcomed part of the proposed project, which is estimated to total $356 million to $400 million. Stretching between Columbia and Manns Harbor, half in Tyrrell and half in Dare counties, the proposed project would widen the road to the north or the south, or if necessary, it could zigzag either direction to avoid conflicts. Most of it will include a 46-foot median, except for a section in Dare that will be 23 feet, the minimum required.

But the need to determine the route of bridge corridors through environmentally and culturally sensitive areas in both counties has resulted a dizzying array of confusing and complicated options. Divided into sections that are often layered or crisscrossed, numerous maps detailing the 17 possible alternatives mixed and matched in various combinations illustrate the hundreds of pages in the 3-inch thick document.

In a resolution sent to DOT in February, East Lake residents asked the agency to build the so-called southern bypass alternative in order to spare their community the loss of 12 of the community’s 62 residences and its historic churches, community center and fire tower. The northern alternative, which is more costly, would impact about 23 acres of refuge land.

Doshier said that East Lake people are mostly blue collar folks who could never afford to be relocated. The community, which has no cable TV and just recently got Internet access, is one of the poorest in the county. But it’s got deep roots and tight family connections.

“You love it,” she said, “or you just don’t live there.”In Tyrrell County, widening to the north would result in fewer relocations of homes and businesses, but going to the south would avoid the Alligator community and create less impact to wetlands and other natural resources. Additional concerns include impacts to J. Morgan Futch Gamelands and other managed lands, and to natural resources protected under the state Coastal Area Management Act.

By law, the refuge manager must determine whether a project that affects Alligator River refuge is compatible with the mission of the 154,000-acre refuge before a permit is issued.

Scott Lanier, deputy refuge manager, said that the refuge would need to see exactly how much DOT would stray from its right of way before a determination can be made. Consideration would also be given to whether certain conditions and mitigation can compensate for the land use.

“There is a means that they can do that,” he said. “These have to be minor modifications that are essential to safety.”

Minnie Spruill, who is one month shy of 89 and East Lake’s oldest resident, said that DOT should do what was done a little further west in Creswell, where the highway bypassed businesses and homes.

If not, she worries that she would be forced to sell her home to the government.

“It’s all about the animals,” she said, speaking in a thick native coastal Carolina accent. “But wherever they lay down is their home. We only have one house. It seems like the animals matter more than the people. It’s the truth.

“I just don’t understand why they’d want to tear down people’s homes with as much land as they have.”

But Lanier said that it is not clear what DOT is planning, and the refuge can’t respond to a proposal until more is known. It appears, he said, that about 100 to 130 acres of refuge property could be affected by the project.

“In a nutshell,” he said, “we need more detail — exactly where do you want to put it? DOT needs to demonstrate to us that they’re using their right of way to the fullest extent possible.”

Thursday: The project’s other potential effects

- Are those evacuation numbers for real? See Todd Miller’s blog, Sounder.

These options would require relocating two churches and the community center in East Lake as well as almost 20 percent of its houses.