Last of two parts

MANNS HARBOR — Back in1995, then-Gov. Jim Hunt reiterated his earlier promise to four-lane U.S 64 from Raleigh to Manteo by 2005. All of it has been done except the last 28 miles between Columbia and this community perched on edge of mainland Dare County.

Supporter Spotlight

Even so, the once 6-hour slog from the beach to the state capitol now averages a breezy 3.5 hours.

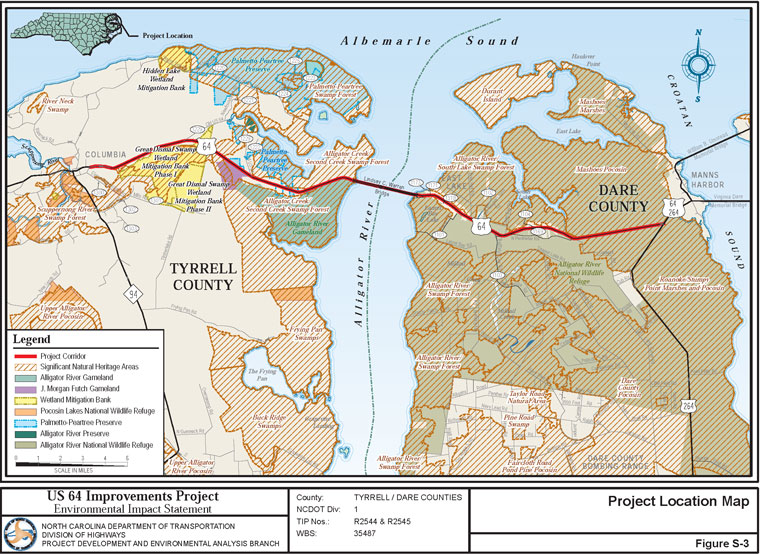

The N.C. Department of Transportation plans on fulfilling Hunt’s pledge and shaving a few more minutes off the trip by completing that last section of U.S. 64. The agency says that the road must be expanded to four lanes to prevent accidents and make hurricane evacuation faster. A draft environmental impact statement was released last month.

The study includes 19 different alternatives and outlines numerous conflicts and tradeoffs.

In Tyrrell County, for instance, northern alternatives would result in fewer relocations of homes and businesses, but going to the south would avoid the Alligator community and create less impact to natural resources. Other concerns include impacts to the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge, J. Morgan Futch Gamelands and other managed lands, and to wetlands, Outstanding Resource Waters and other natural resources protected by federal or state laws.

“We are encountering complex and seemingly competing environmental laws,” said Ted Devens, DOT’s project manager. “I think one of our challenges is to bring all the stakeholders to the table and seek an appropriate balance that reflects the least environmentally damaging and practical alternative.”

Supporter Spotlight

From Columbia to the Alligator River bridge, Devens said, most of the conflicts are less complicated and more manageable. But on the Dare side of the river, it seems nearly every conflict imaginable comes into play.

There are issue pitting federal and private property rights and conflicts with historic and cultural features. In East Lake, DOT may have to contend with the Environmental Justice Act, a federal law meant to lessen a project’s environmental effects on poor and minority communities, and the National Register of Historic Places, which protect historic buildings.

There are red wolves and red-cockaded woodpeckers that are protected under the federal Endangered Species Act. There are protected wetlands in nearly every direction. Depending on the alternative chosen, the widening could affect as few as 40 acres of wetlands to as many as 100 acres.

And as hard as it is to contemplate, there are deep, mucky canals that will have to be relocated. That means the canals lining the road, which are essential for drainage, will be have to be dammed, pumped out, mucked out, filled and re-dug alongside whatever new road configuration is built.

But that’s not all.

“Construction will be difficult,” Devens said, not surprisingly. “We are considering sea- level rise with this design. So the new highway will be at least four feet higher than the existing highway.”

And that means, he said, that while the new highway is being built up, largely from the muck pumped out of the canals, the still-open old highway will be four feet lower in elevation. Temporary barriers will have to be placed between the old and new roads.

New wildlife crossings, small tunnels to large openings, will be installed that allow animals to pass under the highway, rather than risk an unfortunate encounter with speeding tires. The design has been effective in Washington County, Devens said.

Two earlier academic studies had determined animal activity along the road. Dead animals struck by vehicles numbered in the thousands every year in both counties, including deer, bear, fox, bobcat, raccoon, wild turkey, snakes, frogs, turtles and “a surprising number of birds of prey,” Devens said. One red wolf was found dead last year. Just in Tyrrell County alone, for example, seven bear, 885 turtles and 25,000 amphibians — and many equally unlucky snakes apparently in pursuit — were killed on the 55-mph road over a 2-year period.

“Right now, the highway has no permeability for wildlife,” he said. “We feel that if we do this right, this road will represent an enhancement over the existing conditions.”

But the main purpose for the road widening is hurricane evacuation, Devens said. The project has been designed to allow 18 hours, night or day, from the first car to the last car, a timeline that is legislatively mandated.

Construction of the 3.1-mile Lindsey C. Warren Bridge over the Alligator River is targeted to begin in 2014 and be completed in about two years, Devens said. The Tyrrell County half of the road is expected to start in 2016 and the Dare County half should start in 2018. Both ends of the highway will each take about two years to complete.

When the bridge is completed, it will look a lot like the Virginia Dare Memorial Bridge, with its high span, but it will have a wider bike lane.

East Lake residents just hope their community will still be there at the foot of the new bridge.

“I tell you, my home — I don’t worship it,” said Minnie Spruill, who is just shy of 89 and East Lake’s oldest resident. “But my home is priceless to me as long as I’m here. My home is for the family. I said, ‘They can’t give me enough money.’”

Open houses on the draft environmental study will be held April 23 at Columbia High School auditorium and on April 24 at East Lake Community Building from 4:30 p.m. to 6:30 p.m., with a formal presentation at 7 p.m.

- Are those evacuation numbers for real? See Todd Miller’s blog, Sounder.