HOLDEN BEACH – A terminal groin would benefit a handful of homes, protect less than $1.2 million in tax revenue over 30 years and push chronic erosion at the east end of Holden Beach to spots further down the barrier island, according to coastal and economic experts.

Fiscal and environmental perspectives of the town’s proposed $34.4 million terminal groin project were presented during a public forum attended by nearly 100 property owners at the Holden Beach Chapel last Friday night.

Supporter Spotlight

The draft Environmental Impact Statement – a study put together by a consultant firm hired by the town – makes optimistic assumptions, minimizes project costs and does not address uncertainties of the proposed project, said Doug Wakeman, a retired professor of economics at Meredith College in Raleigh.

“Anticipate that the benefits will be lower, the costs will be higher and the uncertainty will largely be ignored,” he said.

The study, which was released for public review last fall, states that 150 properties are at risk along the ocean shoreline in Holden Beach.

Andy Coburn, the associate director of the Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines at Western Carolina University, calculates that number to be much lower.

“A terminal groin, if it’s built and if it does exactly what it’s supposed to do, which it won’t, is supposed to protect all 150 properties,” he said.

Supporter Spotlight

Those properties are seaward of a state-delineated 30-year imminent risk line, and a terminal groin, he said, will not protect all 150 properties, if any at all. By his calculations, the benefits of a terminal groin may accrue to only 32 properties classified as imminent risk.

Over a 30-year period, the projected life of the proposed project, those 32 properties would result in a net present value tax revenue loss of less than $1.2 million, Coburn said.

The net present value tax revenue loss over a 30-year period for all 150 properties is about $5.3 million, he said.

The preferred project alternative in the study would expand 1,000 feet at the Lockwood Folly Inlet with 300 feet anchored on a portion of the large sand spit at the east end and the remaining 700 feet offshore.

The project’s proponents say a terminal groin would offer a long-term solution to chronic, severe erosion on the east end. Over time, the encroaching Atlantic has claimed numerous homes. Houses that were once second-row homes along McCrary Street are now beachfront properties.

Town Mayor Alan Holden, who did not attend the forum, said in a previous interview that dozens of homes on the east end have been lost to erosion.

The town’s consultants on the proposed project, the town manager and the company that conducts the town’s annual beach monitoring reports were invited to be part of the forum. They either declined or did not respond, according to Tom Myers, the president of the Holden Beach Property Owners Association.

Myers said the forum, hosted by his group, the N.C. Coastal Federation and the Southern Environmental Law Center, was held in response to a survey conducted last fall that revealed nearly half of property owners said they needed more information about the proposed project.

A similar Duke University survey, released late last week, reached the same conclusion. That survey states that there is a “mixed level of understanding of beach erosion and the impacts of terminal groins” and that property owners wanted to know more.

Decisions about terminal groins are being made in towns throughout the southern N.C. coast after the N.C. General Assembly in 2011 repealed a nearly 30-year-old ban on hardened beach erosion control structures. Legislators changed the law in 2015 to allow for up to six terminal groins.

Holden Beach, the neighboring barrier island of Ocean Isle Beach in Brunswick County and Figure Eight Island, a private barrier island in New Hanover County, are in various stages of the process of obtaining permits to build terminal groins at their inlets.

Construction of a terminal groin at Bald Head Island, another Brunswick County barrier island, is well underway.

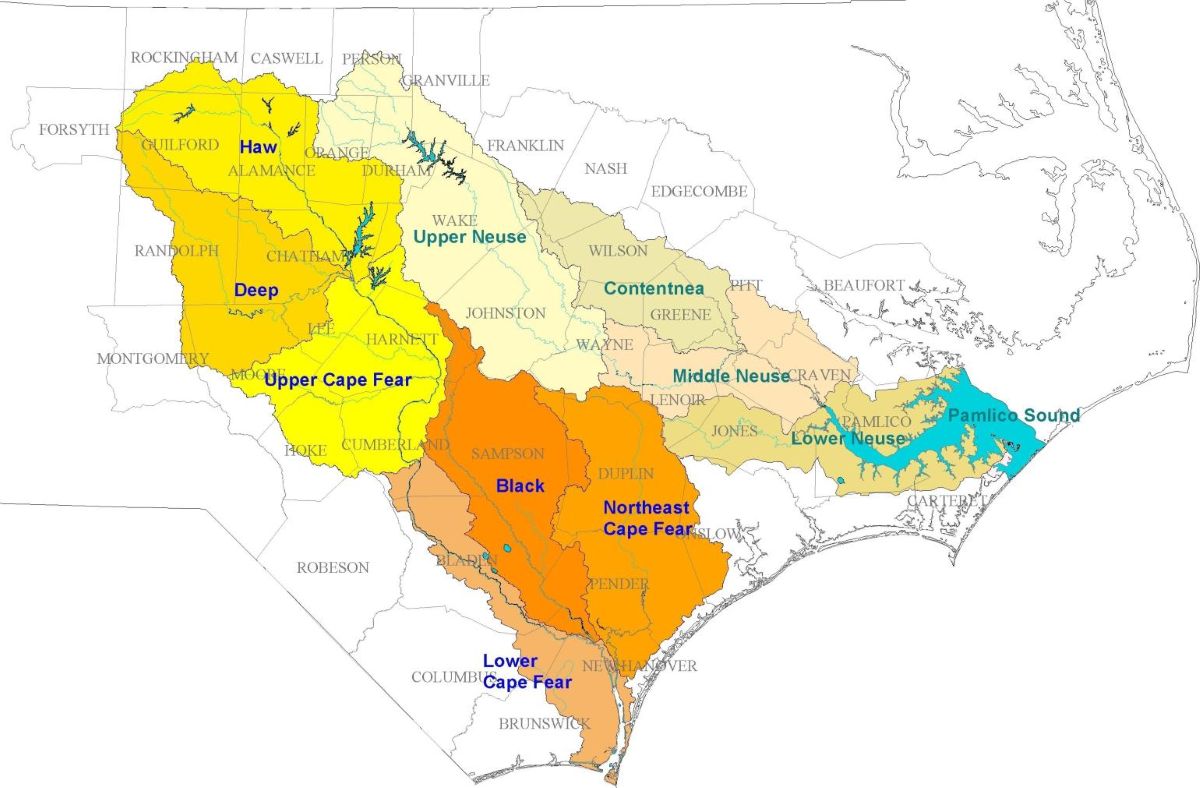

Stan Riggs, a coastal geologist and distinguished research professor at East Carolina University, said that the trouble with building terminal groins is that their potential effects are not isolated to one area, but rather the state’s entire coast.

“This is not only an incredible coastal system, it’s an incredibly complex coastal system,” Riggs said. “The problem is everybody zeros in on one inlet. That’s like looking at one tree in the forest.”

Holden Beach is part of a barrier island system in which 75 percent of the islands are considered “simple” barrier islands. These are low, narrow, sediment-poor islands Riggs calls “mobile piles of sand” and “energy absorbing sponges for the ocean.”

The challenge with building structures on these islands is that people are putting “absolutes” on land that shifts and changes, he said.

“Those islands have been changing forever and they’re going to continue to change,” Riggs said. “They’re storm dependent.”

Storm surge creates the inlets at these islands. Inlets are like safety valves in that they act as outlets, allowing water pushed by powerful storms over and around barrier islands toward the mainland by storms to flow back out to sea.

Lockwood Folly Inlet is one of the more stable inlets along the N.C. coast, Riggs said. “If you close it and lock it down the storm surge can’t use that as a safety valve,” he said.

There are nine hardened erosion control structures along the state’s coast. Riggs showed how two of those structures, both terminal groins, have worked over the decades.

The terminal groin built in the early 1960s in Beaufort Inlet at Fort Macon has shifted the erosion downstream, requiring regular dredging and pumping of sand onto Bogue Banks, Riggs said.

A terminal groin built in the late 1980s at Oregon Inlet to protect the southern approach to the bridge over the inlet has created a sort-of erosion domino effect, Riggs said.

“The rest of the island is collapsing all the way down to Rodanthe,” Riggs said. “Every example we have has never solved an erosion problem. It just pushes it down the island.”

His prediction for Holden Beach is that the same will happen if a terminal groin is built at Lockwood Folly Inlet.

“We need to let the natural system work a little bit,” Riggs said.

He asked property owners to think about how they can live and move with the island.

“We moved a lighthouse,” he said, referring to the 1999 relocation of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse. The lighthouse, facing an encroaching ocean, was moved 2,900 feet inland from where it had stood since 1870.

“We can move anything,” Riggs said. “I want you to think about that because it’s more than just about that one little structure and a few houses.”

Some property owners and town commissioners already have raised concerns about how a terminal groin may affect the town’s proposed “central reach” project. This $15 million beach re-nourishment project would be the largest in the town’s history, placing up to 1.31 million cubic yards of sand along four miles of shoreline.

The town board is currently discussing how to pay for the proposed project, which would be funded through a property tax rate increase.

Commissioners have not discussed how the town would pay for a terminal groin.

Geoff Gisler, a senior attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center, said, if you assume the four-year modeling in the draft study is correct, a terminal groin would protect only about five or six houses at the east end.

“If you read (the study) you might think of this as an existential threat of the whole island,” he said. “The model does not consider storm impacts. They’re only looking at chronic erosion. Although it describes ongoing and chronic erosion, the historical rates at the east end of the island are five to seven feet at the end of the year.”

The model in the study creates a much higher rate of erosion – 20 feet a year.

“None of the alternatives protect all of the houses,” Gisler said.

Town Commissioner John Fletcher said he is not yet prepared to state whether or not he supports the proposed project. “I think we still have a lot more to learn about,” he said.

It is unclear when the Army Corps of Engineers will release the final EIS.