Sand bags attempt to slow down erosion at the east end of Ocean Isle Beach. Photo: Kirk Ross. |

OCEAN ISLE BEACH — Since the N.C. General Assembly passed a bill last year allowing four terminal groins along the beach — the first hardened structures allowed on the North Carolina oceanfront in three decades — the path from concept to concrete has been strewn with questions starting with where they might be built.

Now, with the four projects identified — Holden Beach, Figure Eight Island, Ocean Isle Beach and the Village of Bald Head Island — the questions have focused on how to measure the groins’ effectiveness, their environmental impact and who pays and who benefits.

Supporter Spotlight

A recent analysis by the N.C. Coastal Federation of property ownership in the vicinity of one project highlights that the direct benefit of groins can be highly concentrated.

The analysis, which looked at 631 properties listed in the Inlet Hazard Area around a proposed terminal groin at the easternmost end of Ocean Isle Beach shows that 82 percent of the acreage represented is owned by companies connected to one prominent family.

Properties held by three companies owned and managed by the family of the late Odell Williamson, a longtime civic leader and one of the original developers of Ocean Isle Beach, make up 61 percent of the Inlet Hazard Zone properties, including roughly 100 now-submerged properties that remain on the land records.

According to federation Policy Analyst Ana Zivanovic-Nenadovic, of the roughly $33.3 million of the $82 million in already developed properties at the end of Ocean Isle Beach is owned by the Williamson family and its companies along with much of the remaining developable land.

Todd Miller |

Todd Miller, executive director of the federation, said the study came out of a look at possible relocation of homes, one alternative to building hardened structures.

Supporter Spotlight

Miller said that so much of the property in the area of the groin was found to be controlled by one group of investors raises old concerns about who is benefiting from beachfront projects and new worries about how the legal framework around terminal groins will play out.

Under the Corps of Engineers rules, Miller said, lands conserved through beach re-nourishment are considered public property if public money is spent on the project. But it’s unclear, he said, what would happen to property saved through a groin project, including some of the now submerged properties.

Further, Miller said, the law allows landowners who lose property due to the groins to seek damages. The proposed location for the groin bisects a group of properties owned by one company, LW Legacy Assets LLC, raising the prospect that without some kind of legal agreement with the town, the company could profit on one side of groin by seeing properties become buildable again while seeking damages for properties damaged by the loss of sand flow on the other side. The company is owned by Williamson family members.

“Without some kind of agreement,” Miller said, “they could benefit both ways.”

Take a short walk down the beach at the eastern end of the island and it’s not hard to see why the town and its homeowners are worried. The ocean is carving away at sandbag walls, first installed in 2001. The beach, in places, is heavily scarped. The tide claws at the steps to one three-story home and surf splashes through the carport of another. Occasional bits of asphalt and rock from the ocean front streets crumbled by steady tides and storms poke through the sand.

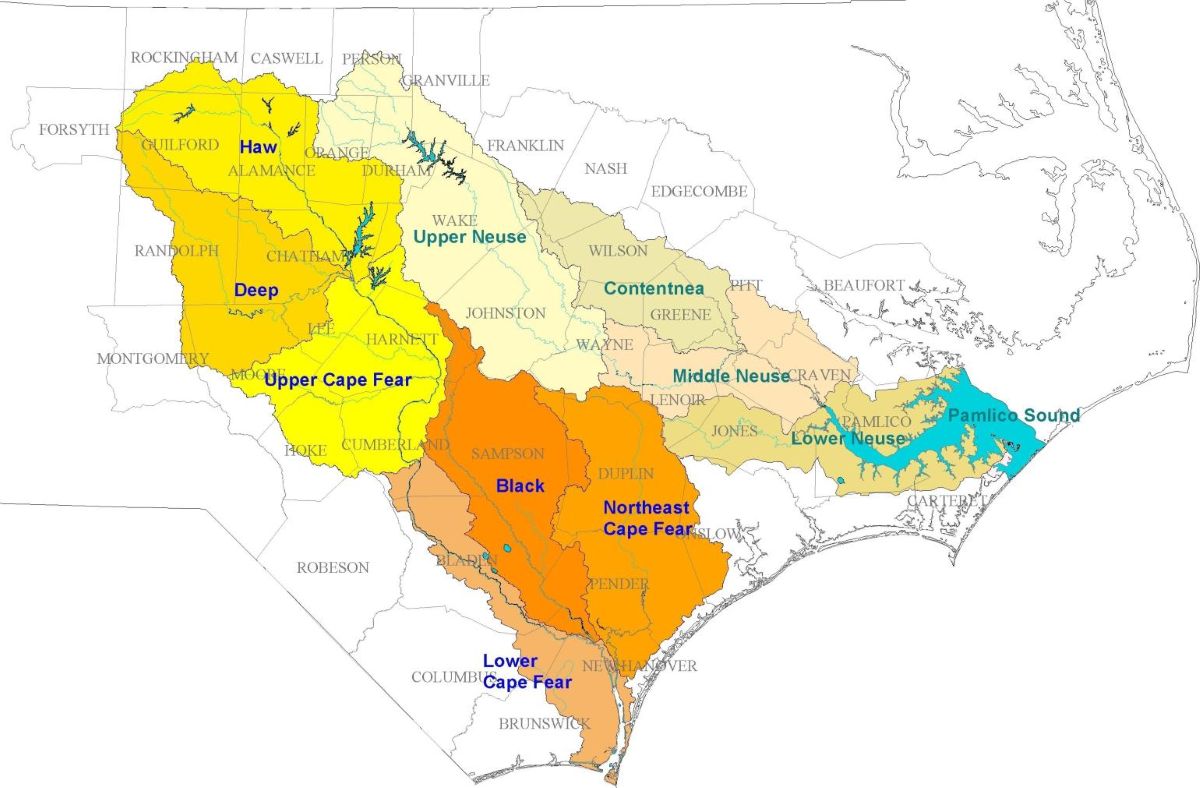

The map show the three companies that own the majority of properties near the proposed terminal groin. Source: N.C. Coastal Federation. |

Mayor Debbie Smith said the groin represents the most promising change in the town’s long battle with erosion. “Those houses you see on the oceanfront were not built as oceanfront homes,” she said. “They were three or four rows back. There’s been a tremendous loss off the end of the beach.”

She said the town is aware of the land ownership concentration, but says the effects of beach loss extend far up and down the eastern portion of the island.

“It’s pretty important,” she said of the groin project. “Not just to the number of private structures, but to the public structures.”

The town, she said, has a major sewage system lift station near a highly scarped point in the beach along Third Street. The station serves dozens of homes east and west of it, Smith said, and losing it would be costly.

Saving the lift station as well as the rest of the town’s roads and infrastructure in the area is one of main goals for the town. So is long-term cost. Beach re-nourishment, Smith said, has proven increasingly expensive and frustrating, especially considering Shallotte Inlet’s hunger for sand.

“You know where it all goes. It all goes right back into that inlet,” said Smith, who has lived in Ocean Isle Beach most of her life.

The hope, she said, is that not only will the groin help stabilize the area, but will make it possible to reduce the frequency of re-nourishment.

Debbie Smith |

She said the town has yet to see a cost estimate, but that there’s a willingness to consider ways to have those who benefit most pay more for the project, a point raised during town discussions on the groin last year.

“I don’t think anything is off the table at this point,” she said. “That’s certainly a model that’s been used up and down the coast.”

Smith said the town recently hiked its public accommodations tax to help pay for the project and will use those proceeds along with money from the tax typically used for beach re-nourishment to cover the costs.

The town has so far budgeted $785,824 for work on preparing an environmental impact statement.

Smith said the time and equity issues are just some of the issues over the groin. The town is also dealing with anxious homeowners worried about the time it will take to work through the process. “They’re frustrated,” Smith said.

The area needs a long-term fix, she said.

Meanwhile, the tide continues to roll. “We had some high water last night,” Smith said on Monday. The result, she said, was a damaged sewer line to the easternmost home on the fast changing ocean front. “We condemned it this morning.”