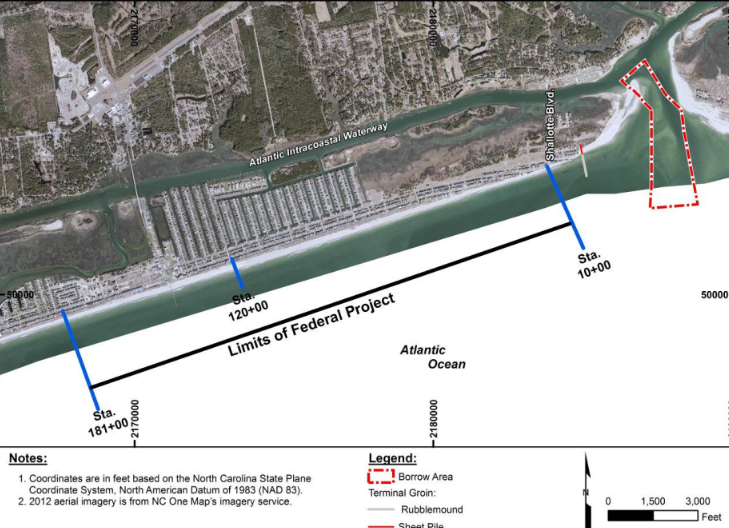

OCEAN ISLE BEACH – Relocating the Shallotte Inlet channel, rather than building a terminal groin, would spare local property owners millions over the long haul and greatly reduce negative effects on wildlife at Ocean Isle Beach’s east end, according to a coastal environmental group.

The Southern Environmental Law Center on behalf of the North Carolina Coastal Federation sent a letter to the state coastal permitting agency arguing that, for those reasons, it cannot lawfully issue a permit for Ocean Isle Beach’s proposed terminal groin project.

Supporter Spotlight

The letter, submitted earlier this summer to North Carolina Division of Coastal Management Director Braxton Davis, describes how the town’s Coastal Area Management Act, or CAMA, major permit application fails to meet federal and state environmental policies.

Ocean Isle Beach Mayor Debbie Smith defends the town’s pick for a shoreline-management project that includes a 750-foot terminal groin with periodic beach nourishment.

Sand injections at the east end following routine dredging of the inlet by the Army Corps of Engineers have not helped curb the chronic erosion on the east end of the island, Smith said.

“That sand is usually gone within a month or two,” she said. “I haven’t seen anybody from the Southern Environmental Law Center down here at the end of that beach and watch that sand put there drift right back into the inlet.”

Smith said a terminal groin would reduce the need for beach nourishment from every three to four years to six or more years.

“From an economic and environmental standpoint, that is certainly a positive,” she said. “It saves money and there’s less dredge terms.”

Supporter Spotlight

Geoff Gisler, senior attorney with the law center, said the final environmental impact statement, which examines a handful of project alternatives, shows that relocating the channel would result in a buildup of the beach at the east end of the island.

Relocating the channel, the fourth of five alternatives included in the study, will be cheaper for town taxpayers, addresses current erosion problems and will maintain the recreational beach and wildlife habitat at the east end, he said.

“Based on what they projected in the EIS it’s going to cost the town $4 million more to build a groin than it would to do channel relocation,” Gisler said. “That’s for the 30-year cost. What does that $4 million get you? The answer is a lot of uncertainty.”

A terminal groin is a wall-like structure made of rock or other material placed perpendicular to the shore adjacent to an inlet to control erosion.

One of the ongoing debates about this hardened erosion-control method is what effect a terminal groin has in creating down-drift beach erosion. In coastal states, including Florida, there are cases where terminal groins have been tagged as the source for significant down-drift erosion.

“You can’t cure erosion because there’s only so much sand,” Gisler said. “It’s quite likely that there will be more extreme erosion on other parts of Ocean Isle Beach or other beaches down.”

The proposed terminal groin the town is seeking permits to build will cost an estimated $45.8 million over 30 years. The projected federal share – an estimated $23 million – will cover routine beach nourishment, according to the study. The non-federal share is $22.8 million.

Channel relocation will cost an estimated $53.15 million over 30 years with the federal share priced at $30.89 million and non-federal share at $22.26 million.

A channel relocation project would cost the town about $9.8 million, according to the study. Since North Carolina law requires towns to pay for terminal groins out of local coffers, the cost to Ocean Isle Beach to build one is about $13.5 million.

That’s a 130 percent greater cost than maintaining the status quo and nearly a 40 percent greater cost than channel relocation, Gisler wrote in his letter to DCM.

Gisler stresses the federation’s concerns that the beach east of the proposed terminal groin’s location will erode away.

“The terminal groin is not a good investment economically for the town and it’s certainly not a good environmental outcome,” Gisler said. “There are some things that are fairly certain and that would be that the habitat is going to be negatively affected.”

The study, prepared by Coastal Planning & Engineering of North Carolina, grossly underestimates the impact the proposed groin will have on the beach, according to the federation. The study analyzes five years of a 30-year project.

Gisler argues in his letter that the beach east of the terminal groin will erode “hundreds of thousands of cubic yards” each year, wiping out the recreational beach and wildlife habitat.

Terminal groins are “intended to stabilize dynamic systems and, in doing that, destroy habitat,” Gisler said.

In its biological opinion of the proposed project, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service states that the agency expects direct and indirect, long-term effects to sea turtles, including loggerhead critical habitat. Fish and Wildlife also point out that shore stabilization projects “fundamentally alter the naturally dynamic coastal processes” that create habitat for federally endangered piping plovers.

Relocating the channel would not only avoid eliminating the eastern end beach, the project would create a larger beach, Gisler wrote.

Smith refutes his argument.

“That’s a highly volatile tip of the island,” she said. “It changes. It always changes. It’s subject to over wash. It’s subject to erosion. It’s subject to build back up. A terminal groin is not going to wash that end of the island away, period, and the modeling does not show that. They have their opinion and I have mine, but I do not feel they have grasped the what the EIS says.”

The Division of Coastal Management has allowed extra time for the public to review the environmental study. Doug Huggett, manager of major permits and federal consistency at the division, said in an email that the town’s permit application was accepted as complete June 10. The division on Aug. 24 extended the permit review for additional 75 days.

The state’s deadline for rendering a decision on the permit is Nov. 7, “although we anticipate that final action on the permit application will take place prior to this date,” Huggett wrote.

The North Carolina Division of Water Resources on Aug. 11 issued a 401 Water Quality Certification for the proposed project. This refers to Section 401 of the federal Clean Water Act, which requires that an applicant for a federal permit certify that any discharges into U.S. waters comply with the act and state water quality standards.

Ocean Isle Beach is one of three southern North Carolina beach communities actively pursuing federal and state approval to build terminal groins.

Bald Head Island, also in Brunswick County, has completed the first phase of its terminal groin project. Figure Eight Island, a private beach in New Hanover County, submitted its CAMA major permit application earlier this year.

Holden Beach, another Brunswick County town, is waiting for the release of its FEIS.

The North Carolina General Assembly initially allowed permitting for up to four terminal groins in 2011 after reversing a decades-old ban on hardened erosion-control structures on the coast.

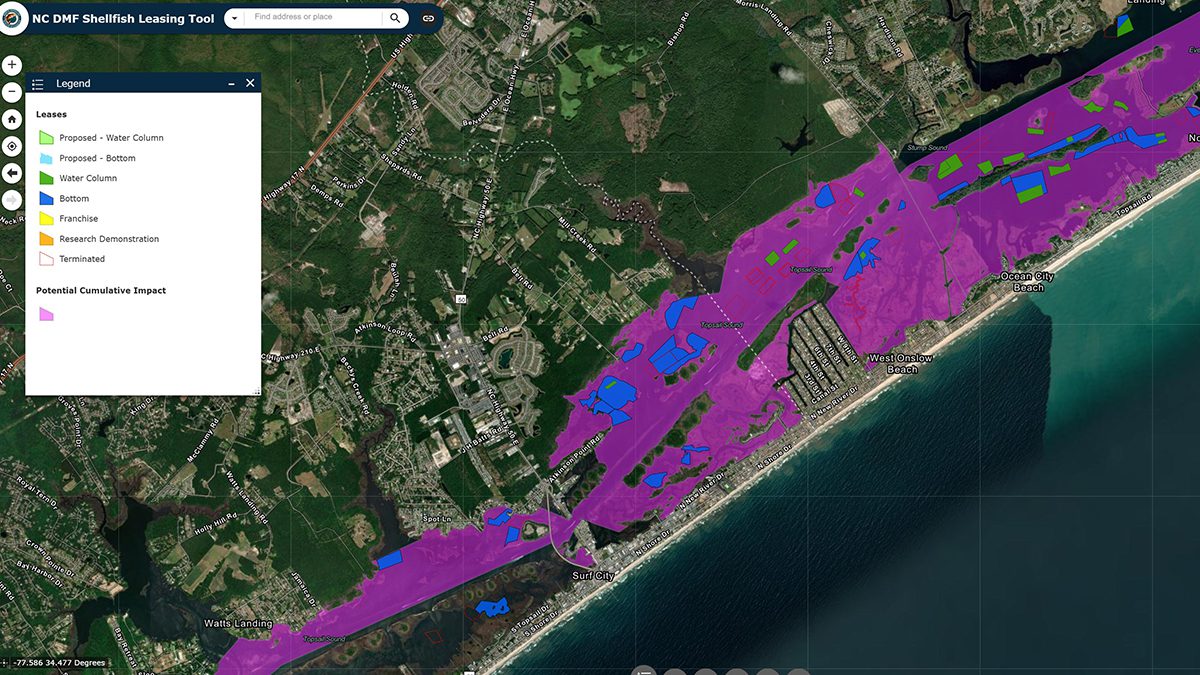

Last year, lawmakers allowed for two more. North Topsail Beach in Onslow County and Emerald Isle in Carteret County were specified in the law, but only North Topsail Beach is currently considering proposals for a terminal groin. Officials there are working on an agreement with the county and neighboring Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune to share the costs of a hardened structure at New River Inlet that would curb erosion and also improve navigation in the inlet.